“After the Last Border: Two Families and the Story of Refuge in America” by Jessica Goudeau. Viking Books (New York, 2020). 334 pp., $27.

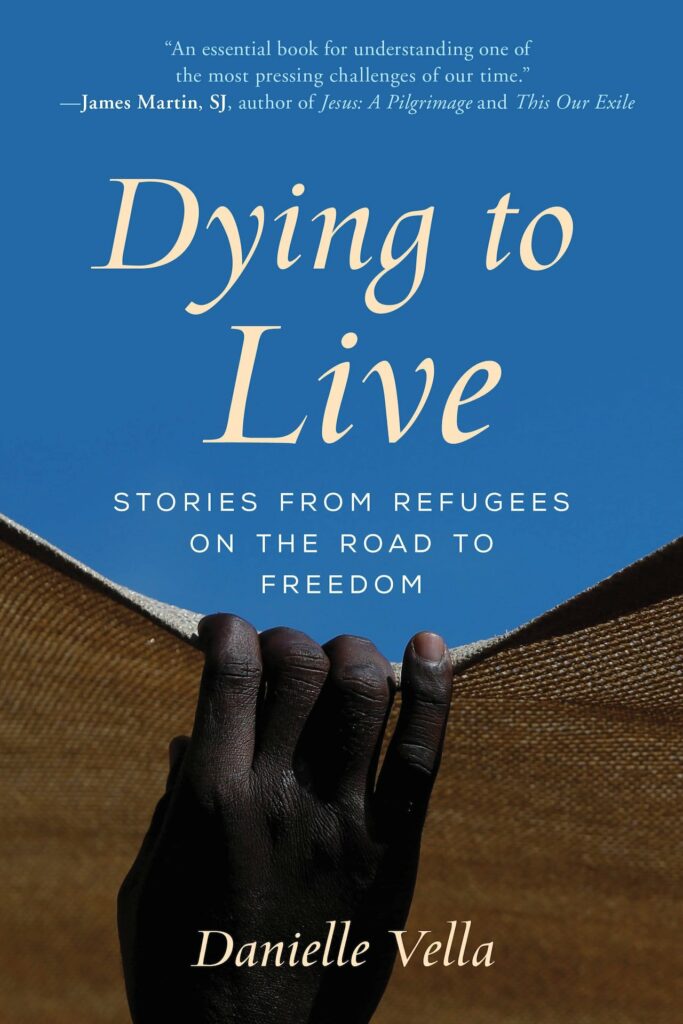

“Dying to Live: Stories From Refugees on the Road to Freedom” by Danielle Vella. Jesuit Refugee Service and Rowman & Littlefield (Washington and Lanham, Maryland, 2020). 204 pp., $26.95.

Two new books offer poignantly illuminating stories about refugees whose stories will undoubtedly resonant with readers.

“After the Last Border: Two Families and the Story of Refuge in America” and “Dying to Live: Stories From Refugees on the Road to Freedom” describe in vivid detail all the stress, anxiety, pain, fear, hope and disappointment families face while journeying toward resettlement.

Their stories are impactful and bring to the forefront the deserved dignity and true humanity of every refugee life.

Often in American media and politics, the topic of refugees is handled numerically. Refugees are referred to in measurable phases to control and account for the ebb and flow of resettlement. Numbers are easy to divide, monetize, budget, stack and shelve away.

And author Jessica Goudeau in “After the Last Border” smartly harnesses this familiar quantification throughout her book to frame the two families she features within a historical context. But their stories cannot be shelved away. Her powerful writing simply won’t let them.

Goudeau highlights the physically and emotionally draining trek of two remarkably brave matrons of refugee families, Mu Naw, a Karen Christian from Myanmar, and Hasna, a Muslim from Syria.

At age 5, Mu Naw experienced her first border crossing. A little girl, she ran with her family and fellow villagers from the ethnic cleansing of the Burmese junta. She remembers her parents angry and battered.

Mu Naw’s father suffered pain through their panicked flee, his leg previously blown off by a land mine. Her mother is frightened and bitter. This early memory is the first of many in her childhood observing panic-stricken, anxiety-ridden adults, makeshift homes in camps, and a broken family strained by the stress of war. Eighteen years later, Mu Naw, a young mother herself, eventually is resettled as a refugee in Austin, Texas.

Although the illusive American dream teases readers to believe her story ends there, it does not. The scars of trauma do not fade so easily, and her new city and community is not always welcoming and safe. Her life gives witness to the deep wounds of war and resettlement and that evil and sin exist even in safe places.

Hasna’s story contrasts from Mu Naw. By the time she reaches Austin, she is an older mother resettling with her husband and her teenage daughter, the youngest of her six children. Her other children by that time were already dead or displaced, as nothing remained of her beloved grapevine-shaded, jasmine-scented home in Daraa, Syria.

At one time, Hasna welcomed her large and extended family to her large courtyard filled with begonias, lemon and olive trees. Her tiny, musty apartment in Austin by way of Jordan was a dismal reminder of a life forever gone.

Goudeau, who has written for The Atlantic and The Washington Post among others, gives these stories the platform they deserve, providing eloquent details that only a talented writer with intimate knowledge of her subjects can provide. Goudeau, who has worked with refugees for more than 10 years, is the co-founder of Hill Tribers, a nonprofit organization that provides supplemental income for refugee artisans.

Unlike Goudeau, Danielle Vella in “Dying to Love” is much more raw, straightforward and blunt. Frankly, it is a hard read for the unprepared. Vella intermingles throughout the book a weaving of quotes and firsthand accounts of devastating stories of kidnapping, abuse, horror, violence and death. Not for entertainment, nor intended as a gentle nudge toward awareness, this is an alarm call of the realities that exist in the world.

Vella, who is the director of the International Reconciliation Program for the Jesuit Refugee Service, honors refugees by allowing them the space within these pages to share their experiences. As the refugees recall their personal histories, they are shared through direct quotes, regardless of their harsh content or literary flow.

Take, for example, Habib. Drugged and kidnapped as a 10-year-old, he spent 15 years imprisoned in Algeria among other places. He shares how he was beaten, desperate to escape, and longingly anxious to find out what happened to his parents.

Salma, a mother from Syria, recalls the food shortages that nearly starved her family. The lines of hungry civilians queuing outside the bakery had become neatly formed targets for bombing. In the book she says, “Sometimes, my children came home with bread spattered with blood. … They would give you just four flatbreads, but we had five children.” Salma would disguise herself to return to the dangerous lines to get more bread to feed her family.

Like “After the Last Border,” “Dying to Live” does not console readers with happy endings of welcoming homes in Europe and the United States. In their new resettlements, these refugees also meet confusing new lives, isolation, racism and anxiety.

Yet in lieu of easily forgotten consolation, “After the Last Border” and “Dying to Live” instead imprint on readers the knowledge that refugees are not the quantifiably unnamed. They are Mu Naw, Hasna, Habib and Salma.

Lordan, a mother to three young children, has master’s degrees in education and political science and is a former assistant international editor of Catholic News Service. She currently teaches and is a court-appointed advocate for children in foster care.