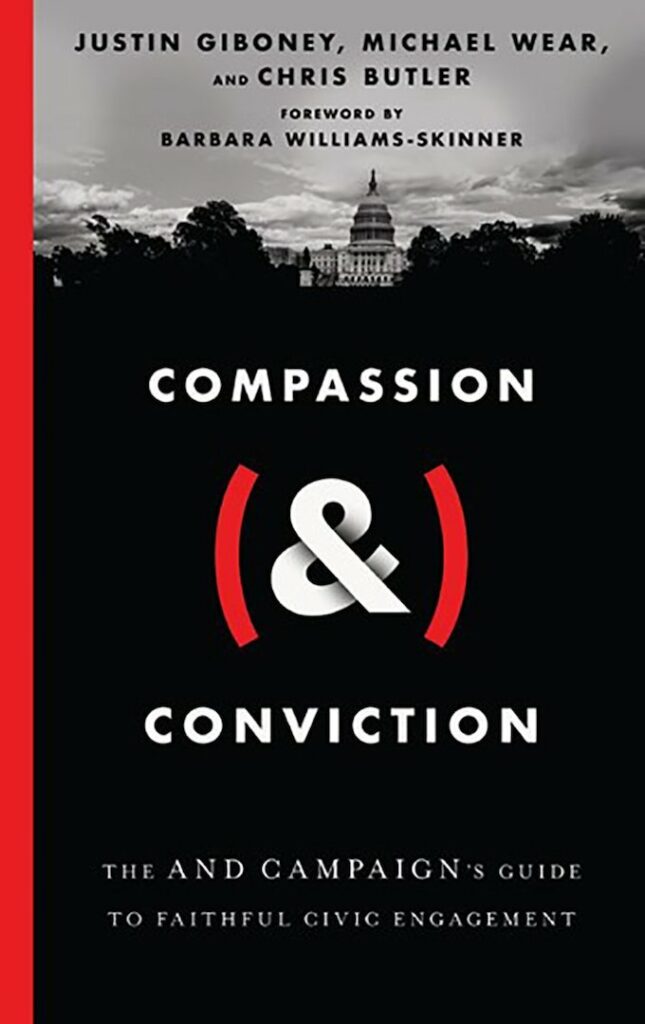

“Compassion (&) Conviction: The AND Campaign’s Guide to Faithful Civic Engagement” by Justin Giboney, Michael Wear and Chris Butler. InterVarsity Press (Downers Grove, Illinois, 2020) 146 pp., $22.

This excellent book comes at an important moment in our nation’s history and should be read by all.

It encourages readers to be civil with one another, whatever their political views, and to work together for the betterment of all Americans and for our country as a whole. We are in a most divisive moment in our country’s history.

This is a guidebook for Christians to reach deeply into the best of our biblical traditions and the teachings of Jesus to come together in peace and respect. We must reach across the political, racial, social and religious divides, as the Bible challenges us to do.

Fortunately, the book also provides guidelines for groups of people with differing views to come together. It gives readers numerous examples of Christians throughout our history who have worked with others to help those in need and to render their communities and the whole nation a better place in which to live.

Each chapter has a dual title: Christians and Politics, Church and State, Compassion and Conviction, Partnership and Partisanship, Messaging and Rhetoric, Politics and Race, Advocacy and Protest, Civility and Political Culture. Think both/and rather than either/or, leading to the campaign’s name of AND — or (&).

In encouraging us to bring our differences to the table of dialogue, the authors — an attorney, a political strategist and a pastor — also insist, rightly, that we should listen to the others around us, question them so we can fully understand what they are trying to communicate.

Only then should we bring up to the others our own views and possibly differing understandings of the situations facing our communities and our country, and how best to promote the common good of all Americans.

The book contains refrains that remind us that the “dialogue must be civil.” It also contains statements which, as a biblical scholar, I would amend or phrase differently.

For example, the authors cite the Gospel of John, chapter 12, about “the Pharisees.” In point of fact, Jesus did not speak against “the” Pharisees as such. Rather, he engaged in dialogue within the Pharisaic movement, siding except for divorce with the followers of Hillel.

A century before Christ was born, Hillel interpreted the Bible’s commands according to their spirit, teaching his followers to deepen their understanding of its meaning and reach out to those in need, to work for “tikkun olam,” the healing of the world. Jesus argued against the literalist and minimalist interpretation of Rabbi Shammai, another Jewish scholar of the first century.

The distinction is important, since Judaism, which was the religion of Jesus, has followed the Hillel approach to this day, which can provide a solid basis for working with Jews on what is in fact a common understanding of social moral teaching. Such an outreach can also provide a common ground for working with the followers of other religions as well.

I also would note the disagreement between Peter and Paul discussed in the section on “Confronting Racism” was not about “race” as we understand it today. In fact, “race” did not gain the meaning it has today until the age of Enlightenment.

In Europe, the other “race” was the Jewish people. In America, racism meant discrimination against African Americans. In the former it was the basis for modern racial anti-Semitism, which was used to justify the barbarities committed against Jews and paved the way for the Holocaust. In America, it was used to justify the depravities of slavery.

The argument between Peter and Paul was over the question of whether gentiles who converted to nascent Christianity had first to be converted to Judaism, using the rituals such as the “mikvah” (total immersion) and an oath of loyalty to the Jewish people and to the one God (“Your people shall be my people and your God my God”).

Paul argued that gentiles could directly become Christians without adhering to the whole of the biblical laws (Jews count 613 laws).

In their “closing exhortation” the authors conclude: “Our purpose in civic engagement is not to make our own names great but to make known the greatness of the One who sends us. Our great desire is to be agents of the will of God in the earth, distribution centers for the love of God toward his creation.”

Fisher is a professor of theology at St. Leo University in Florida.