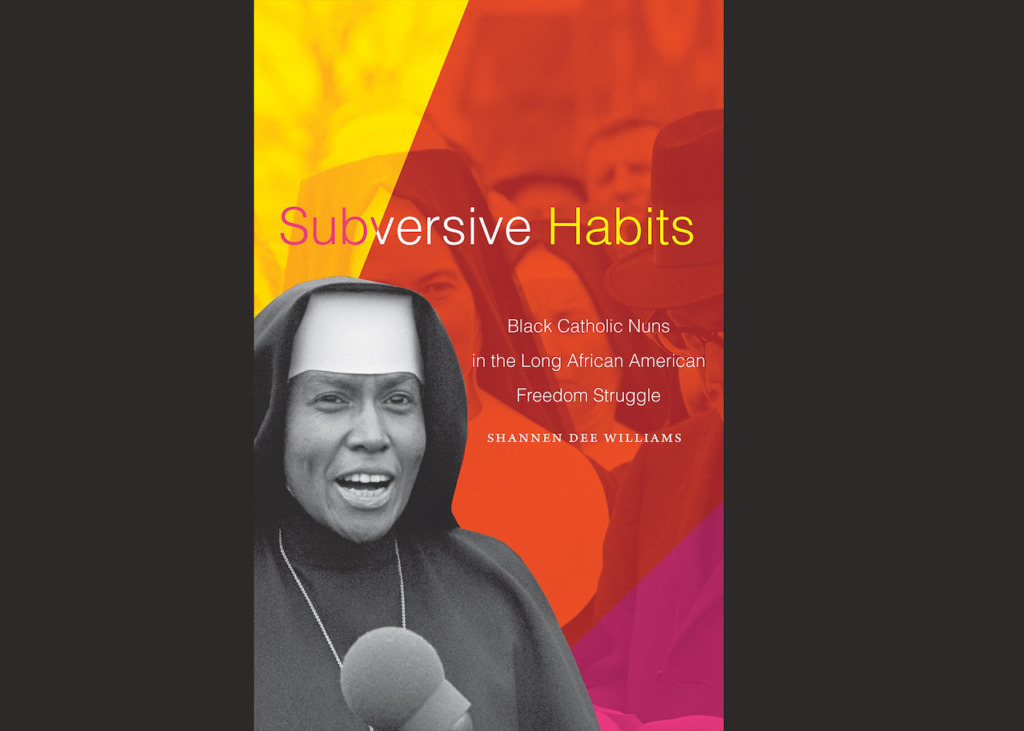

“Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle,” Shannen Dee Williams, Duke University Press, 2022, 424 pages.

In her book “Subversive Habits,” Shannen Dee Williams, a professor of history at Ohio’s Dayton University, explores the history of Black Catholic religious sisters in the U.S. from the 17th century to contemporary times.

Meticulously researched and fully supported by use of archival material, primary sources and interviews, “Subversive Habits” is the product of nearly 14 years of study, research, writing and revision. In essence, Williams argues that the Catholic Church in the U.S. has long been complicit in oppressing Black Catholics, especially women in religious orders. To the church’s shame – and owing to the undeniable fact that influential religious communities (for example, the Jesuits and the Daughters of Charity) did in fact purchase and trade enslaved peoples – Williams describes the church as one of the largest corporate institutions of enslavement in the United States.

The pioneering Black women religious of America, many of whom were barred from entering white communities based entirely on the color of their skin, are the fascinating and inspiring heroes here, persevering in their vocations even when (in the few instances where Black nuns gained admission to white-led orders), they were often mistreated or relegated to subservient roles.

The book can be a gripping read, as Williams tells the stories so many Black sisters had kept to themselves for too long. It offers especially inspiring insights into their lives, not least the dynamic Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman, and Sister Mary Antona Ebo, who participated in the 1965 civil rights march in Selma, Alabama, telling the assembly there, “I’m here because I’m a Negro, a nun, a Catholic, and because I want to bear witness.”

The book sheds new light on the struggles of religious sisters to establish and operate Black-only schools and colleges. “Most of the nation’s Catholic colleges and universities – all led by white priests and sisters – upheld the racial status quo during Jim Crow and placed Black congregations in an extremely precarious position in the era of teacher reform and private school accreditation,” Williams writes.

Williams charges church leaders of the time with erasing or revising historical records of Black religious communities, not only to hide their influence but also to exaggerate the importance of white women religious in building the church throughout North America. In addition, Williams uncovers several episodes of Black applicants to convent life being seen as immoral, promiscuous and “unworthy of the habit.”

But it is William’ title, “Subversive Habits” that adds poignancy to these religious sisters’ efforts to shake off longstanding oppression and remain faithful to the church. Williams believes that many Black sisters and their leadership recognized early in the game that by persevering in the struggle to form their own communities or to integrate all-white orders, they kept alive hopes for a more equitable church and a less patriarchal society.

The book’s one weakness may reside in the author’s tendency to assume the motivations of individuals and entire communities. In discussing white Catholic reactions to the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, for example, Williams writes, “Although [Black Catholics] and their forebears had exercised heroic patience in their individual and collective battles against anti-black racism in their church, Black Catholics knew how culpable white Catholics were in fomenting and legitimizing the racial hatred that killed King.”

Nevertheless, “Subversive Habits” serves to fill historical gaps and omissions that have obscured anti-Black racism as “a defining feature” of U.S. Catholicism and its attitude toward Black women religious. In a damning indictment, Williams believes the Catholic Church – through its involvement with the slave trade and its failure to integrate faith-filled Black Catholic sisters into the wider community – can be seen as “the first global institution to declare that Black and Brown lives did not matter.”

“Only when Black nuns and other Black people, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, dared the Church to live up to its core principles of universal humanity and acknowledge (however grudgingly) that the lives and souls of Black people mattered did the white-dominated Church reveal its capacity for becoming truly Catholic,” Williams concludes, adding, “The same can be said for the nation at large.”

This is heady stuff for Catholics taught to uncritically support the universal church and respectfully honor the clergy. But if any rapprochement is possible, it begins with examining church history as it is and promoting a sense of contrition (coupled with real atonement for all wrongs, past and present) within the church, and with seeing church oppression of Black Catholics as indelibly linked to our nation’s long struggle with racial justice.

Mike Mastromatteo is a writer and book reviewer from Toronto.