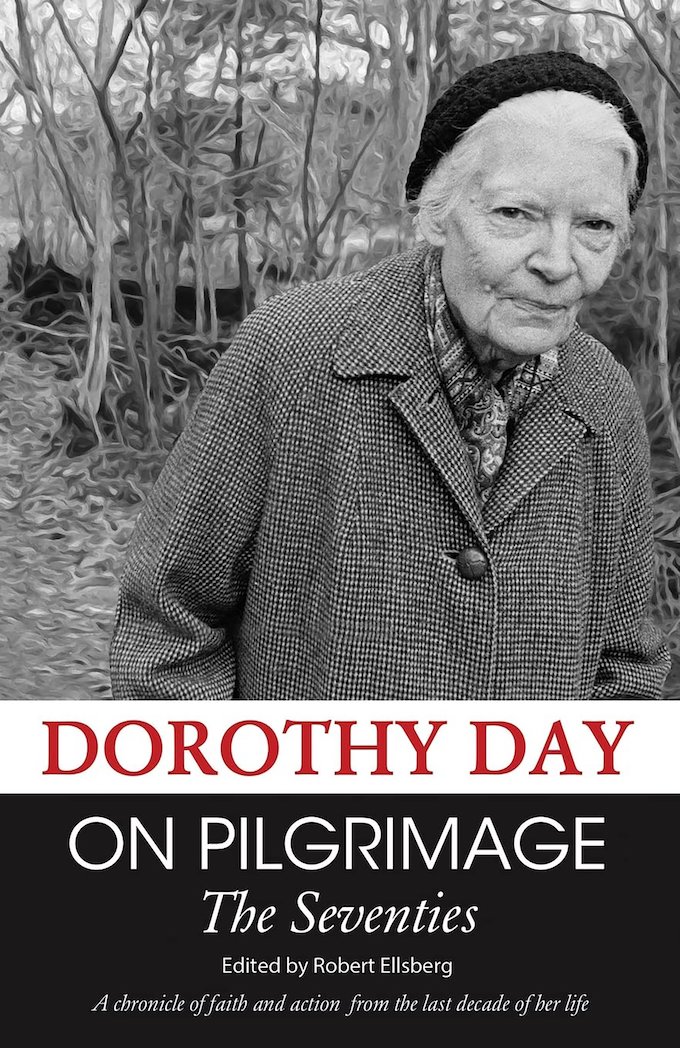

“On Pilgrimage: The Seventies” by Dorothy Day; edited by Robert Ellsberg. Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York, 2022). 274 pp., $28.

This collection of Dorothy Day’s columns from the last decade of her life demonstrates her heartfelt commitment to her faith and to social justice and peace. Weakened by heart disease, she nonetheless continued to take part in protests and arrests (including her final one at age 75, in 1973 with Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in California). She also helped found a shelter for homeless women, Maryhouse, in New York City.

There she died in her room at the age of 83 on Nov. 29, 1980. Subsequently, the historian David O’Brien called her “the most significant, interesting and influential figure in the history of American Catholicism” and a movement for her canonization has gathered speed.

Today the story of Day’s co-founding of the Catholic Worker movement and its newspaper in 1933 and her decades of activism are well known. Perhaps less familiar is the final phase of her earthly pilgrimage, when she continued to cultivate a deep Catholic spirituality and consistently practiced solidarity with the poor and dispossessed.

This anthology of Day’s writings from that period, carefully curated by Robert Ellsberg, illuminates how she remained faithful to her faith and to her long-standing commitment to help create a better world even as her physical strength ebbed.

Arranged chronologically, the selections are enriched by Ellsberg’s informative introductions. For instance, he prefaces her Catholic Worker column from January 1972 with a note about her long-standing support of Chavez and the United Farm Workers union: “In Chavez, a devout Catholic and a follower of Gandhian nonviolence, she saw not only someone working for justice and better working conditions but also a leader in the work for an alternative society, and the embodiment of an ‘earthy spirituality.'”

Day’s column described a visit she’d made to the farmworkers’ education center in La Paz, California: “Even now as I write I can see the Berlin-like wall, the high riot fencing topped with rolls of barbed wire which separates the barrios of Tijuana from the lush fields of southern California. As far as the eye can see there are those shacks made of cartons and old bits of tar paper and carpeting, wall to wall, the wall of one a wall for the next, acres and acres of destitution.

“Most horrible of all, there is caught in that barbed wire topping the high fence bits of clothing, a sleeve of a coat, a sock, a ragged shirt, caught there and torn from the scratched and bleeding body of some desperate person trying to get over the fence.”

Day wrote eloquently until the end, though as Ellsberg notes, “As she entered the last five years of her life, Dorothy spoke more frequently about slowing down and turning over day-to-day responsibilities to those she called ‘the young people.'”

Thus in her March-April 1975 column, Day portrayed the Catholic Worker as “in a way, a school, a work camp, to which large-hearted, socially conscious young people come to find their vocations. After some months or years, they know most definitely what they want to do with their lives. … They learn not only to love, with compassion, but to overcome fear, that dangerous emotion that precipitates violence.”

The “mild heart attack” that Day describes having in September 1976 “was another signal of her declining energy and withdrawal from public activities,” according to Ellsberg. “Her ‘pilgrimage’ would continue, though now of a more interior nature.”

In an article first published in 1973 (reprinted in the Catholic Worker in May 1978), she observed how “the Poor Peoples’ March on Washington speaks to the world today of the ‘misery of the needy and the groaning of the poor,'” and lamented such current tragedies as “assassinations of national leaders; fear of ‘the fire next time,’ … remembrance of the horrors we have already lived through in this short lifetime – the massacre of the Armenians in World War I; the ghastly and obscene holocaust of the Jews. … And today, the slaughter which is going on in Vietnam.”

But in her Fall Appeal in 1978 she could also observe, “But we would be contributing to the misery and the desperation of the world if we failed to rejoice in the sun, the moon and the stars, in the rivers which surround this island on which we live, in the cool breezes on the bay, in what food we have and in the benefactors God sends.” This simultaneous apprehension of the everyday and the ultimate is typical of Day.

Besides the timeless appeal of Day’s writing, another strength is Ellsberg’s thoughtful introduction. The publisher of Orbis Books lived as a member of the NYC Catholic Worker community during Day’s final five years, including two years as the Catholic Worker’s managing editor.

Perhaps few could give as personal a view of Day in her last years as Ellsberg, who writes with grace and humility: “I didn’t know 45 years ago, when Dorothy had the idea of appointing me managing editor of the paper, that she was also pointing me in the direction of my life’s work and vocation: not just as an editor, but as her editor.”

To the four previous volumes of Day’s writings that Ellsberg has edited, this addition is another gem. Readers will find much here to inform and inspire.

– – –

Roberts is a journalism professor at the State University of New York at Albany and the author/co-editor of two books about Day and the Catholic Worker.