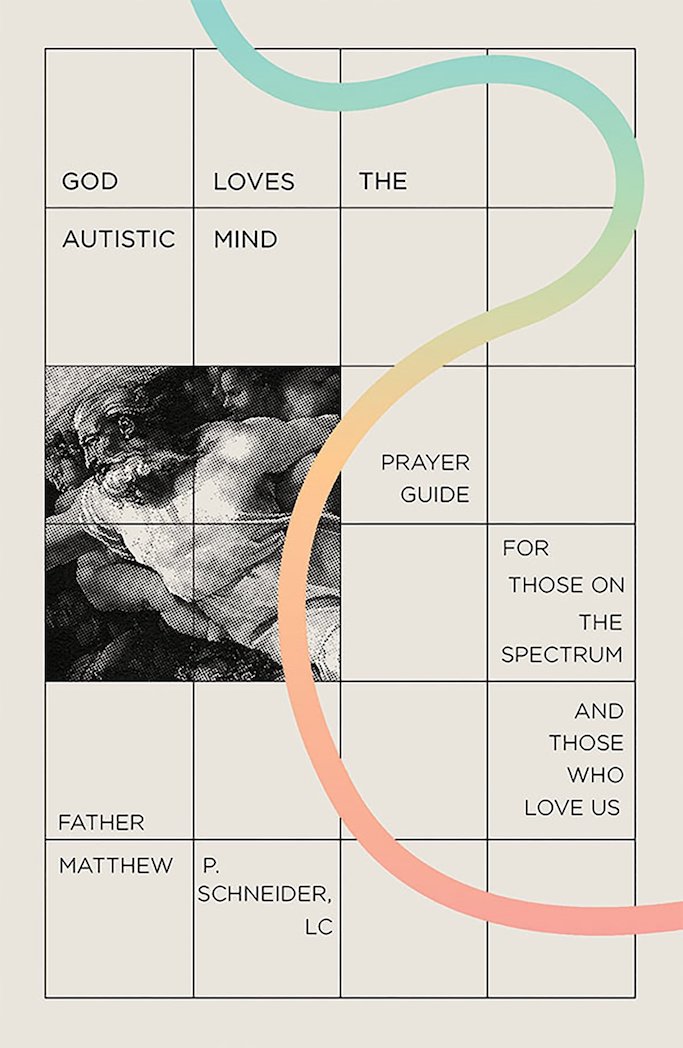

“God Loves the Autistic Mind: Prayer Guide for Those on the Spectrum and Those Who Love Us” by Father Matthew P. Schneider, LC. Pauline Books and Media (Boston, 2022). 211 pp, $16.95.

When one seeks guidance about how to improve in a particular sport, it is preferable to get it from someone who has played that sport. When one seeks guidance regarding an addiction, one who is well into recovering from it is an excellent resource.

Thus, it makes sense for autistic people and their families seeking better ways to pray to get direction from an autistic person, especially when the person giving it is a Catholic priest. That is how Father Matthew P. Schneider, a member of the Legionaries of Christ, sees his goal in writing “God Loves the Autistic Mind.”

The priest begins by sharing his story and giving a summary of how autistic people pray differently than neurotypicals, i.e., those who have a “standard system of connectivity.” The former’s prayer, he notes, focuses on information, while the latter’s is emotional.

He writes, “The autistic logical foundation tends to be more solid than the more emotional foundation neurotypicals may have for their spiritual life. We autistics often need a reason: … If you say I should do X because you say so, I will pretty much ignore you. If you give me a decent reason, I will generally follow through. We need a reason why, but once we have that reason, we remain steadfast in our resolve.”

In the first part of the book, Father Schneider provides an overview — primarily by comparing and contrasting how autistic people and neurotypicals think and how knowing this is critical to their prayer lives. He familiarizes readers with words, e.g., stimming, that are an integral part of the autistic mind.

He addresses myths about autism, including the idea held by some that it is some sort of demonic possession. He relates the story of a woman who was the subject of an attempted exorcism.

He also notes that autistic people, even in adulthood, are likely to pray in a “childlike” manner, which he writes “refers to someone who relates to God simply, a person for whom faith and the spiritual world seem ordinary in this life,” adding that “childlike” is different than the self-centeredness and pettiness of one who is “childish.”

While the first part reads like a research paper, complete with footnotes, the second part of “God Loves the Autistic Mind” is engaging, as it includes 52 mediations, several of which include the personal stories of autistic people, including the author’s, a Scripture passage and a reflection. Topics include “Jesus Loves Me as an Autistic,” “From Loneliness to Being Alone with God” and “Remain Watchful in Our Own Lives.”

Father Schneider considers “God Loves the Autistic Mind” a “first attempt at enculturating the faith to autistics. I don’t expect it to be perfect, but I do intend to keep some important truths in mind: the orthodoxy of the Catholic faith and the reality of being autistic.”

This first attempt is important because of the autistic faithful for whom it was written. However, tighter editing, e.g., elimination of the frequent and distracting use of “I think,” would have made it a better book. Nonetheless, it is eye-opening for neurotypicals and one that autistic people might find affirming in their prayer lives. As Father Schneider writes: “We need to avoid stigmatizing autism and recognize that autistics are called to be and can become saints.”

Olszewski has been involved in Catholic communications for more than 46 years and has reviewed books for Catholic News Service since 1985.