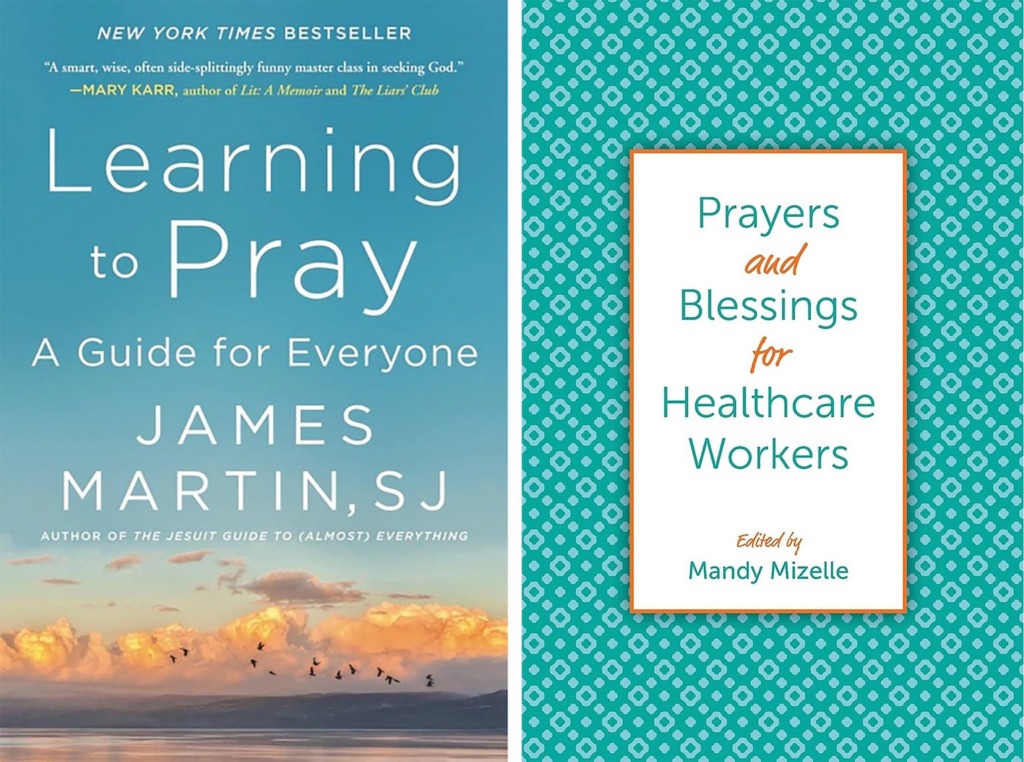

“Learning to Pray: A Guide for Everyone” by Jesuit Father James Martin, HarperOne (New York, 2022). 416 pp., $17.99.

“Prayers and Blessings for Healthcare Workers,” edited by Mandy Mizelle. Morehouse Publishing (New York, 2021). 175 pp., $21.95.

Prayer can be a fierce bombardment, a soft kiss, a hopeless sigh, a victory cry. Or “prayer” can be an act of multiplying words that gains nothing. Jewish philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote, “There are people who pray absentmindedly and often act as if the service of God consisted of manual labor. Obedience is holy. But does God ask for only automatic conformity?”

The perils of prayer haunt and befall all of us. Into this fray two new books on prayer have dropped — “Learning to Pray: A Guide for Everyone” by Jesuit Father James Martin and “Prayers and Blessings for Healthcare Workers,” edited by Mandy Mizelle.

Father Martin writes that prayer is not an “approach from below” but, rather, “a long, loving look at the real.” He saw this truth come alive when he attended an acting class taught by a gifted voice teacher.

The class started with each participant standing alone in front of the others to recite an awkward, simple sentence: “I am here, in this room, with all of you, today.” For the next 30 minutes they did five simple “awareness” exercises that had absolutely nothing to do with vocal chords or enunciation.

After finishing the exercises they again stood individually in front of the group to speak that same dull sentence they had recited earlier. “I couldn’t believe it,” Father Martin writes. “My voice felt completely different. That bland sentence was now invested with meaning. … Each word and phrase meant something. … If you had told me this would happen, I wouldn’t have believed you.”

The teacher explained those five exercises had brought them into the present moment. “Once you are present to what you are saying, you express it differently, and as a result it sounds different.” So, too, with prayer. (This passage is so revelatory and life-changing it should be printed as a church brochure and distributed to every diocese in the country. Until that happens, go to page 133.)

A surprising strength of this book are the many anecdotes that Father Martin stitches into his text. He shares his struggling relationship with a fellow Jesuit who hated him. “He really hated me,” he says, “and we both lived in the same building.”

On a lighter side (maybe), he brings up a Jesuit priest who discovers his mother praying a rosary “against” his cousin Timmy, who had refused to help her with household chores. When the aghast Jesuit tells her she can’t do that, the mother shoots back, “You wanna bet?” Father Martin tells this tale while explaining so-called “curse” prayers and psalms where authors pray for the gruesome deaths of enemies (see Psalm 137).

Turning to our second book, “Prayers and Blessings for Healthcare Workers,” I am staggered by it. A strange osmosis took place as I read this collection of prayers and poems written by those who minister to COVID-19 workers and caretakers. I moved under their lights, shoulder to shoulder with them, enduring just a trickle of the trauma upon trauma they suffer (and still suffer) in hospitals and at their homes.

I keep returning to the poem, “A Tuesday Afternoon in 2020” by the Rev. Laura D. Johnson. She writes about holding the hand of a dying man in his hospital room. The poem is so real and seamless I can’t stay away. Here are a few lines: “His eyes start to close/ His face softens./ I stay there/ and my heart sinks when I tell him/ it’s time for me to go./ I slowly slide my hand out and say,/ ‘I’ll hold you in my heart.'”

The editor of this book is the Rev. Mandy Mizelle, a United Church of Christ chaplain and retreat leader who lives in North Carolina. Last year she became a Decedent Care chaplain. (Decedent means a person who has died.) Most mornings she goes to the morgue to place a death certificate with a body before a funeral home or crematorium takes it away.

“I am there to honor the bodies made of dust and divinity,” she writes. “Squatting on my heels at the foot of each gurney, I offer a prayer or a blessing, depending on what I know of that body, the spirit that inhabited it, the people and places it touched, the ones it loved. Afterward, I make my way back to the land of the living.”

From “They Say This Time Is Invaluable” by Leenah Safi, who is gazing at “a woman who doesn’t look comfortable in her skin anymore,” her dying mother: “Death/ Smells horrible — even from a distance/ It clings to everything/ Your senses know/ existing in this atmosphere/ is like having a larger-than-life ‘houseguest’ that won’t leave/ but graciously insists you carry on.”

There are 54 contributors to this book, including mental health advocates, a former Oklahoma state poet laureate, a presiding Episcopal bishop, a Muslim doctoral student, a rabbi and Christian ministers of all faiths from Baptists to the United Church of Christ.

From “Companioning One” by the Rev. Arianne Braithwaite Lehn: “Reground my understanding/ that while I am called to faithfulness/ with what I have,/ where I am/ the make-or-break power of my days/ is beyond my skill./ Give me one reminder this week, God,/ of your presence in the details –/ just enough to shake me from/ this stupor of self-reliance.”

Holy medals come in all shapes. The prayers and blessings in this book are holy medals etched with the faces and hearts of those who die and those who save.

“Learning to Pray” and “Prayers and Blessings for Healthcare Workers” have a “pick-up-and-read” quality. They induce a fervor in readers to enter their closets and pray on their own. Here’s praying they never go out of print.

Cubbage has written for Notre Dame magazine and for several national Catholic newspapers and magazines.