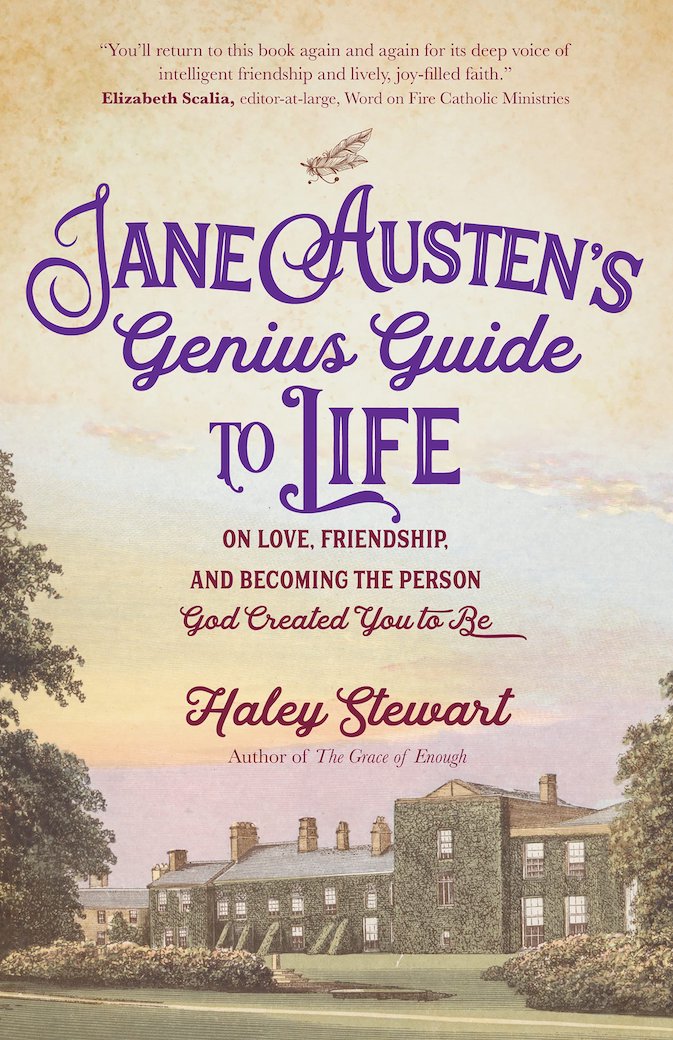

“Jane Austen’s Genius Guide to Life: On Love, Friendship, and Becoming the Person God Created You to Be” by Haley Stewart. Ave Maria Press (Notre Dame, Indiana, 2022). 160 pp., $16.95.

If you’re surprised by the idea of Jane Austen as a life coach, don’t be. After all, the Jane Austen Society of North America has at least 81 regional groups devoted to the writer that host regular book discussions, workshops and celebrations of her birthday.

The timelessness of works such as “Pride and Prejudice,” “Sense and Sensibility” and “Emma” speaks to their author’s deep understanding of human vulnerabilities.

Now Haley Stewart, a Catholic writer and podcaster, unpacks the practical and spiritual wisdom that Austen offers in her six novels. Lively and informative, “Jane Austen’s Genius Guide to Life” gives a uniquely Catholic perspective on the British writer’s exploration of human relationships.

For example, Stewart writes that the character Emma Woodhouse “fails to recognize either the shortcomings of those who flatter her or the potential of friends who might challenge her to improve. She judges others not according to their merits but according to how much they admire and agree with her.”

This self-centeredness leads Emma to reject friendship with Jane Fairfax, a “beautiful and accomplished” orphan, for fear that the woman might “outshine her.”

The takeaway from Emma’s story is that we should strive not to let jealousy and vanity stop us from reaching out to others. As Stewart observes, “Humility is always the turning point in our journey toward virtue.”

In “Mansfield Park,” Austen deals squarely with the conflict between reality and appearance. An attractive exterior may not necessarily be good — and it may not match the character of the interior.

In this novel, Edmund Bertram finds himself unable to resist the charms of a beautiful married woman, and, after hesitating, this leads him to participate in a little home play with her that also involves other young men as well as his young sisters.

This happens while his father is away and it has the potential to create a scandal, because it was then considered unseemly for young women to have such close, unsupervised contact with young men they hardly knew.

Because Edmund “is bamboozled by charm — he does not have the moral strength and courage to stay committed to the right course of action under pressure from others.” But the quiet Fanny Price, whom Stewart describes as the story’s “moral compass,” declines to participate, showing the importance of the virtue of constancy.

As Stewart observes, each of Austen’s novels wittily examines common human vices — and their antidote virtues. Thus “Pride and Prejudice” explores “the consequences of intemperance (Lydia and Wickham), folly (Mr. Bennet and Mrs. Bennet) and selfishness (Caroline Bingley).” The cure for pride, according to Austen, is humility.

Another lesson from Austen the life coach teaches the importance of prudence. For instance, Mrs. Jennings in “Sense and Sensibility” means well but doesn’t recognize that others might be more sensitive than she is to teasing behavior.

And the “lack of a moral imagination” by Catherine of “Northanger Abbey” prevents her from seeing that others may be far more “false, manipulative or conniving” than her own good character allows her to imagine.

Stewart rightly recommends reading “Persuasion,” the last and most mature of Austen’s finished novels, last. Here you’ll encounter the beloved character Anne Elliott, who models the virtue of fortitude.

Life’s slights could have made her angry and bitter, but she chooses to endure her disappointments with grace. She remains open and compassionate toward others, with a strong sense of self.

Stewart likens Anne’s courage to that of early Christian martyrs. While she “is not at risk of execution in the Colosseum by wild beasts,” nevertheless Anne is “‘afflicted in every way, but not constrained; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed'” (2 Cor 4:8-9).

This little gem of a book is thoroughly engaging with wide appeal, including to those who have never even cracked a Jane Austen novel.

An appendix gives pithy plot and character summaries for each of the novels. Another appendix briefly reviews the many film adaptations that have been inspired by Austen’s books. There are also suggestions for further reading and extensive footnotes.

For each chapter, an appendix includes several useful group discussion questions. These reflect Stewart’s wide-ranging background and include thoughtful references and comparisons with Flannery O’Connor, St. Thérèse of Lisieux and others.

Roberts is a professor at the State University of New York at Albany and the author/co-editor of two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.