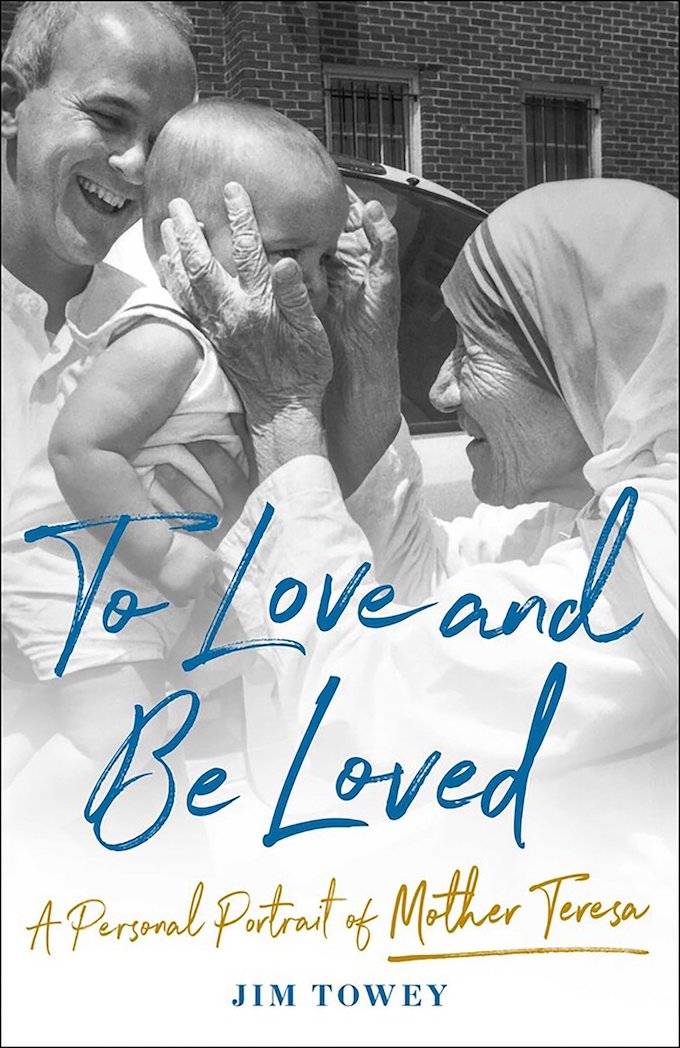

“To Love and Be Loved: A Personal Portrait of Mother Teresa” by Jim Towey. Simon & Schuster (New York, 2022). 288 pp., $27.

St. Teresa of Kolkata (born Agnus Gonxha Bojaxhiu) died Sept. 5, 1997, at the Missionaries of Charity motherhouse in Kolkata, India. The cause of death was heart failure.

During her 87 years, she had become internationally famous as the communities of women and men she founded opened missions around the globe to provide homes for orphans and battered women and care facilities for the destitute dying from AIDS, leprosy and abject poverty. She was declared a Catholic saint in September 2016.

To mark the 25th anniversary of her death, Jim Towey has written “To Love and Be Loved,” offering a brief biography of Mother Teresa from his perspective as her friend – the saint kept a picture of Towey and his family in her desk and she wrote him notes to Jimmy – and as the attorney who provided legal services for her and her communities.

In this personal portrait, Towey describes how Mother Teresa was instrumental in changing his life for the better through her care for the destitute and her life of holiness.

Numerous books have been written about the life and accomplishments of St. Teresa from which Towey borrows (with acknowledgment) to paint his portrait. The book is most interesting when Towey tells of his personal experiences with Mother Teresa (whom he generally refers to simply as “Mother”) and the Missionaries of Charity communities.

From August 1985, when he first met her in Kolkata, until her death 12 years later, Towey learned to care for the sick and dying – and to see them as the personification of Jesus Christ.

After a brief time considering a vocation to the priesthood as a Missionary of Charity, Towey met his wife among the volunteers at their AIDS facility in Washington.

Because of his connections in the U.S. government – he met Mother Teresa because he was a senior adviser to Sen. Mark Hatfield of Oregon – Towey soon was called on to help with Missionaries of Charity legal matters.

In this role, he received frequent letters and calls from her, and he accompanied her on many national and international trips. He was an official delegate to her funeral and proclaimed the first reading at her canonization Mass, so he has many interesting stories to tell.

This is neither a “tell-all” book nor a critical examination of St. Teresa’s life. Towey simply provides a positive message of the “Mother” he knew and loved.

In the chapter where he discusses some of the negative charges leveled at Mother Teresa and her ministries (for example, that her homes for the destitute and dying provided little real medical care), Towey responds with accuracy and understanding that these homes were not meant to be hospitals; rather, they were expressions of Christian charity, providing a place where the dying could be lovingly cared for until death.

While accurate, more thorough critiques on these topics would have been valuable. In addition, the reader would welcome any insights that Towey could offer as to what drove Mother Teresa to expand the Missionaries of Charity outreach across the planet.

On this topic, Towey says next to nothing. These are not deficiencies in the book, only a desire for more. Finally, Towey makes clear that any royalties from the book will be given to charity.

The book is an easy and enjoyable read. While informative, it doesn’t bog down in details or minutia. It deserves to be read and discussed by both religious and secular book clubs, for it raises important issues worthy of discussion.

– – –

Also of interest: “Teresa of Calcutta: Dark Night, Active Love” by Jon M. Sweeney. Liturgical Press (Collegeville, Minnesota, 2022). 184 pp., $19.95.

– – –

Mulhall writes from Louisville, Kentucky.