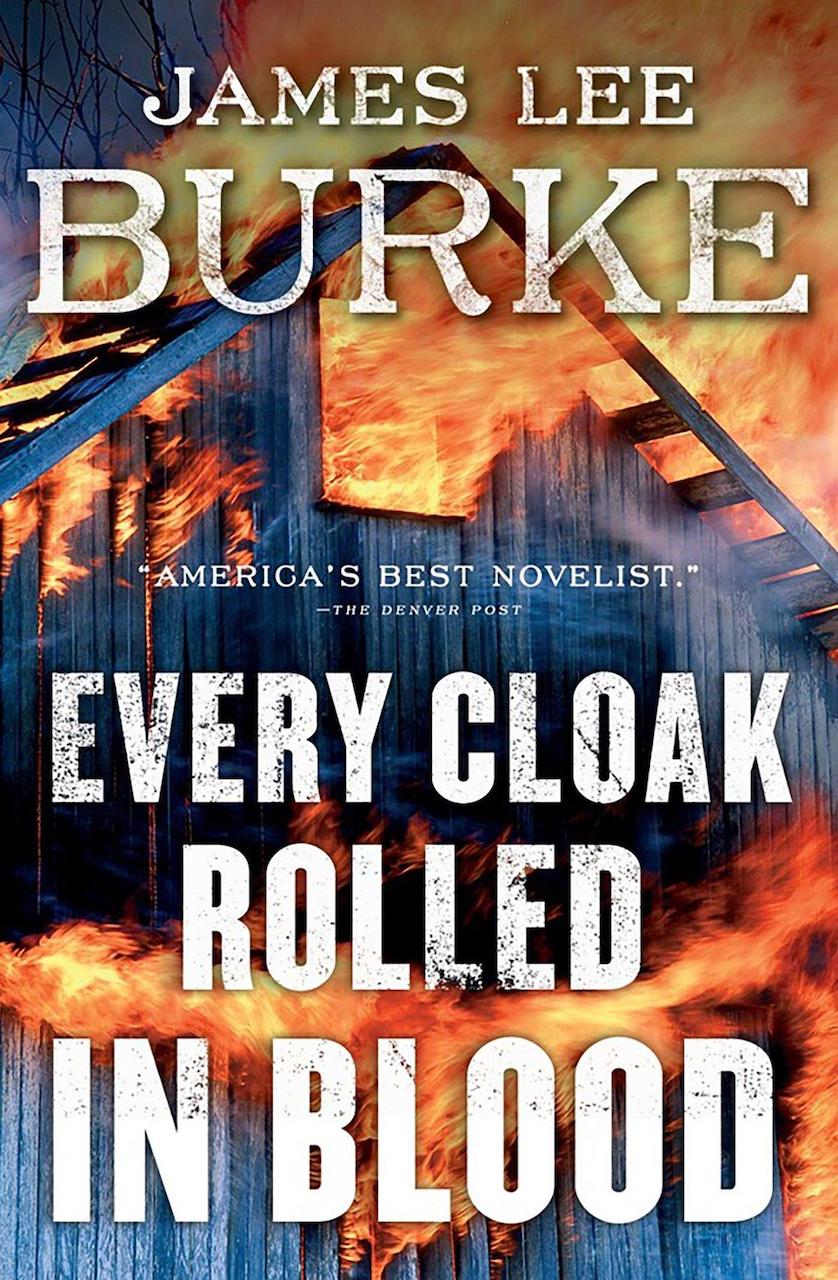

In many ways, “Every Cloak Rolled in Blood,” the 41st and most recent work in the James Lee Burke canon, is similar to his earlier works. At the same time, however, the book is remarkably fresh and new.

Long regarded as a crime writer with an otherworldly bent, Burke’s stories often present an “Everyman” character struggling to cope with the presence of evil, injustice and violence in a despoiled paradise. His latest work continues in that vein, but with an obvious autobiographical flavor.

“Every Cloak” focuses on protagonist Aaron Broussard — a figure appearing in several previous Burke novels — as he struggles with the recent death of his beloved daughter Fannie Mae. Broussard is a Montana-based writer who wears his sorrow against a backdrop of violence, corruption and murder (in the past and to the present day), in a northwestern town beset with drug smuggling, crime and desperately hopeless lives.

The fact that Burke himself is a Montana-based veteran writer who recently lost his daughter, Pamela Burke McDavid, underscores the personal nature of this moving account. In a note to readers, Burke describes his latest work as an attempt to capture part of mankind’s trek “across a barren waste into modern times.”

And while some of the author’s more recent books include deceased characters reappearing with messages from beyond the veil, “Every Cloak” populates the narrative stage with more ghostly characters than living ones.

Much of the drama derives from the eerie appearance of Maj. Eugene Baker, a U.S. Army officer who in 1870 directed his troops to murder nearly 200 Piegan Blackfeet Indians in what is infamously referred to as the Marias (Montana) Massacre. It’s not the first time Burke has brought 19th-century characters back to life in his narratives, but it is certainly the most chilling.

It is the Baker figure who is responsible for the novel’s intriguing title. In response to Baker’s invitation to Broussard to “join the victors” in the second American revolution dedicated to destruction of the inferior, Broussard responds from the Old Testament Book of Isaiah: “For every boot that tramped in battle, every cloak rolled in blood will be burned as fuel for fire” (Is 9:5).

This novel reveals the author’s concerns about divisive political ideology and the danger of mob thinking. In resisting the temptation to lord over the weak and vulnerable, Broussard voices one of author Burke’s long-held themes: “The greatest mystery for me has always been the presence of evil in the human breast. Animals kill in order to survive. The record of humankind is so bad we cannot look at it squarely in the face or dwell on its memory lest we become subsumed by it.”

One gets the sense from reading “Every Cloak” that this is an author nearing the end of his writing life. He discourses on long-held questions and laments the difficulties in acquiring wisdom and understanding in the twilight of one’s life. Despite this troubled perspective, the new book holds out a measure of hope and redemption for those who consider that there just may be an ultimate purpose to human existence.

As Broussard notes late in the novel, “I believe the world to be a cathedral shaped by a divine hand, and if this is true, I should fear death no more than I should returning to the home of my birth.”

Mastromatteo is a writer and book reviewer from Toronto.