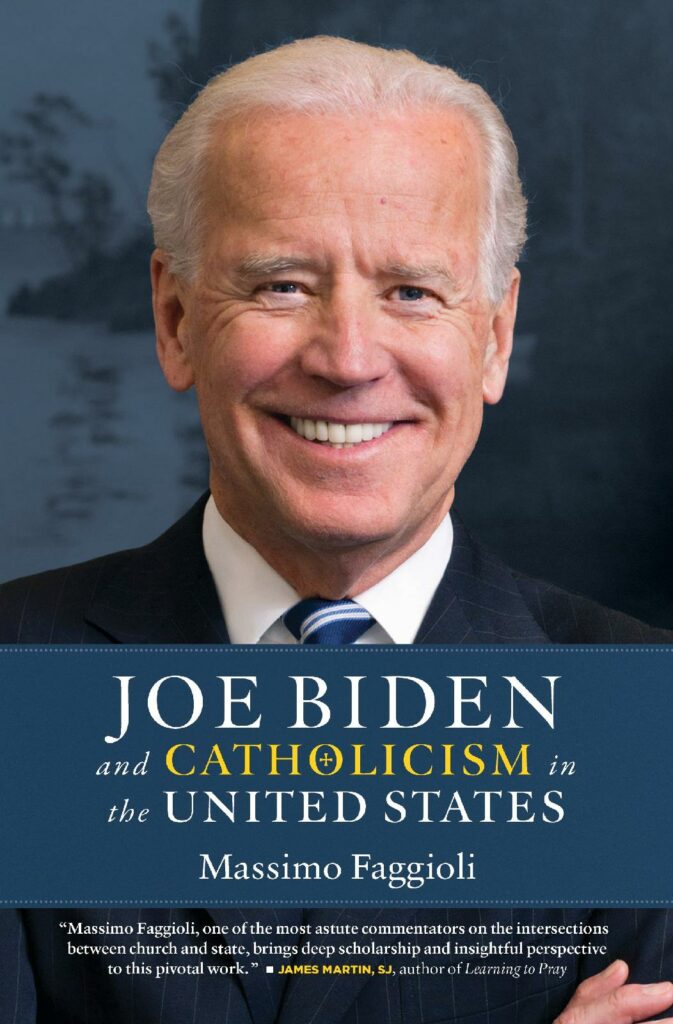

“Joe Biden and Catholicism in the United States” by Massimo Faggioli. Bayard (New London, Connecticut, 2021). 161 pp., $22.95.

Early in “Joe Biden and Catholicism in the United States,” Massimo Faggioli asks, “Why does the election of a Catholic president deserve so much attention?” One can almost hear him replying, “Well, I’m glad you asked,” for he attempts to provide answers to that question throughout this book.

Starting with what he terms “six key issues for American Catholicism in the public square” — “compatibility between ‘papist’ Catholicism and Protestantism; relationship between Roman Catholicism and American democracy; relationship between Church and racism; immigration; role of government and the state; and sexual morality and abortion” — Faggioli, a professor of theology and religious studies at Villanova University, builds a narrative that includes not only the president and country, but Pope Francis and the Catholic Church.

How he connects those four elements is what makes this a heavily academic book, complete with cited sources for much of what is written.

According to Faggioli, having a Catholic president or, more accurately, this Catholic as president, matters because his global vision aligns in multiple ways with the pope’s, while noting the pope’s global vision and the “Make America Great Again” mantra of President Donald Trump were incompatible.

He also posits that Pope Francis and President Biden have one task in common: to explore the meaning and consequences of a world no longer centered on a Western liberal model of civilization.

As critical as Faggioli is of neoconservatives, neotraditionalists, illiberals, Trump and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, he is as effusive in his praise of Biden, whom he describes as “a devout Catholic but not a bigot; his life is marked by mourning, but he is not mournful. His is the faith of a grown-up, lay Catholic, but it is also ministerial and in its own way diaconal.”

Among other opinions Faggioli presents are:

— “Biden’s faith is a credible Catholicism because it is more lived than proclaimed. It makes him culturally compatible with many Americans who may be more conservative but not right-wing. As president and as a Catholic, he faces a religious opposition that is a subset of the North American opposition against Pope Francis.”

— “If there is anyone who represents the future of U.S. Catholicism more accurately (than Biden and Pope Francis),” it is U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y.

— “The face of public Catholicism is now celebrities from the world of entertainment such as Bruce Springsteen, Stephen Colbert and Lady Gaga,” rather than Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen and Father Charles Coughlin, who in their day were popular radio personalities. (The archbishop’s TV fame came later.)

While Faggioli generously sows his opinions throughout the text, there is plenty of scholarship, too. This is particularly evident when he provides the history about the four Catholics who have run as their party’s nominee for president — Al Smith, John F. Kennedy, John Kerry and Biden. The context it provides helps the reader understand what each encountered and the state of the Church at the time he ran.

This book might appeal to Catholics interested in a blend of U.S. presidential history, U.S. Church history and the universal Catholic Church — present and future. It also could serve as a test in civility if people with different views of the president and the Church were to read it and discuss it.

Among those with a different take on some Biden are the U.S. bishops. When it comes to abortion, Biden supports keeping it legal and is in favor dropping the long-standing bipartisan Hyde Amendment prohibiting tax dollars from paying for abortion.

As Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gomez, USCCB president, has noted there are areas “where we agree and will work closely together” with the new administration, and “areas where we will have principled disagreement and strong opposition.”

At the very least, anyone planning to read this book should be familiar with the Second Vatican Council’s “Gaudium et Spes” (“The Church in the Modern World”), Pope Francis’ encyclical “Laudato Si’,” on caring for the environment, and his apostolic exhortation “Amoris Laetitia” (“The Joy of Love”), which followed the synods on the family in 2015 and 2016, as each will provide some context for what is presented as part of the Francis-Biden path.

Those not as immersed in the literature that Faggioli references or to whom terms like “culture wars,” “wafer wars” and “Benedict option” are foreign might have to do remedial reading along the way in order to grasp the entirety of what he is saying.

“Joe Biden and Catholicism in the United States” is educational and thought-provoking, but as his presidency and the Church evolve, readers can be certain it will not be the only book on this subject.

Olszewski is the editor of The Catholic Virginian.