FIRST MISSIONARIES

THE CATHOLIC FAITH REACHES VIRGINIA — IN BLOOD

It may come as a surprise that the origins of Christianity in Virginia are Catholic and Spanish-speaking, not Protestant and English-speaking. The first permanent English settlement in North America was founded at Jamestown in 1607. However, 37 years earlier, Spanish Jesuits had already come to the same land (1570). Their missionary expedition, launched 450 years ago this month, brought the Catholic faith to the territory that became Virginia.

At the time of the Jesuits’ arrival, the European colonization of what became the continental United States was up for grabs. Spain, France and England vied to establish profitable colonies in North America and to spread their religion (Catholic or Protestant). Spain arrived first, calling that territory la Florida because it was discovered during the “flowering” of Easter (1513).

Spanish colonists established various settlements along the east coast of North America, including the first permanent European one at St. Augustine, Florida (1565). Around this time, the Huguenots (French Protestants) sought, unsuccessfully, to plant colonies for themselves in the same territory, and occasionally clashed with the Spanish there (1562– 1565).

After the Huguenot colonists abandoned their settlement at Charlesfort (1562–1563), located on present-day Parris Island, South Carolina, the Spanish founded Santa Elena (St. Helena) on the same site (1566).

Spain became interested in settling the land north of Santa Elena, which the indigenous inhabitants called “Ajacán” (as it sounded in Spanish). This territory eventually became Virginia. The Jesuit expedition to Ajacán left Santa Elena on August 5, 1570.

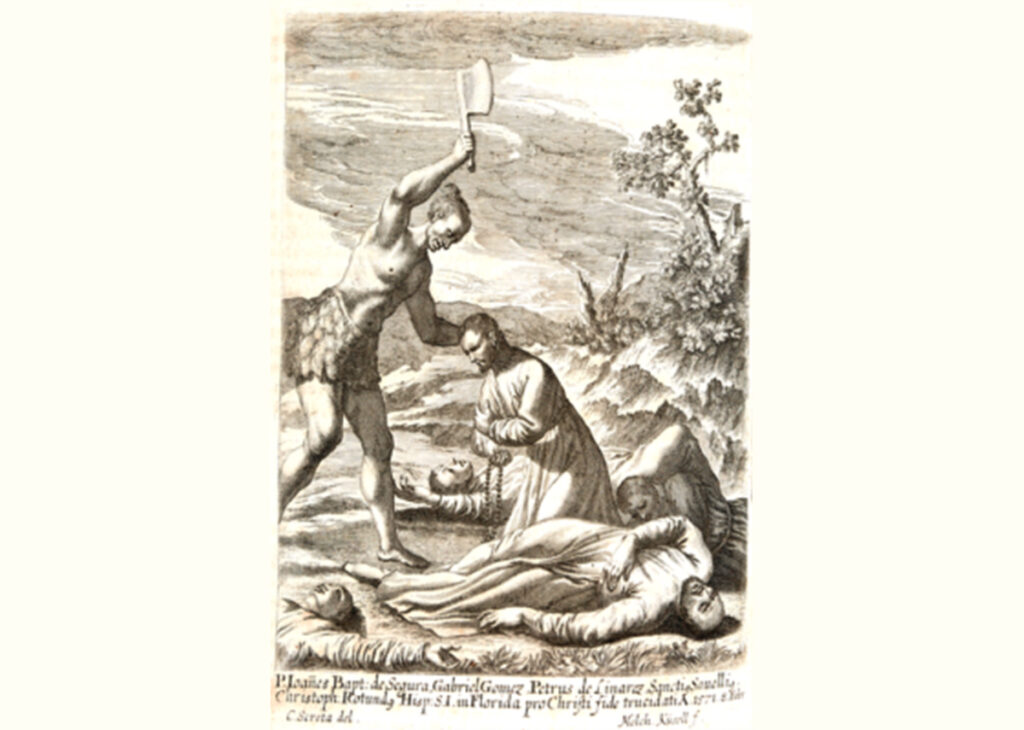

There were nine missionaries. The two priests were Father Juan Baptista de Segura, Jesuit vice provincial of la Florida and leader of the expedition, and Father Luis Francisco de Quirós. There were also three Jesuit brothers: Gabriel Gómez, Sancho de Zaballos and a novice, Pedro Mingot Linares.

In addition, four catechists were part of the group: Cristóbal Redondo, Gabriel de Solís, Juan Baptista Méndez and Alonso de Olmos, the youngest member who was also an altar boy.

Significantly, at Father Segura’s insistence there was no military component to the expedition. Although this was contrary to Spanish practice, Father Segura did not want soldiers to accompany the missionaries because they were known to abuse indigenous people, and in that way to thwart conversions.

The Jesuits’ guide was a member of the Chiskiack tribe of Ajacán: Don Luis de Velasco (formerly Paquiquineo). Although he belonged to a ruling family, he had willingly joined a Spanish fleet a decade earlier (ca. 1561). Subsequently baptized, he took the name of his godfather, the viceroy of New Spain.

Don Luis then crossed the Atlantic to Spain, where he was educated and where he met King Philip II. He returned to North America and eventually guided the Jesuit missionaries to his homeland.

On Sept. 10, 1570, Don Luis and the Jesuits disembarked near present-day Williamsburg. The missionaries built a shelter further inland, and for the next five months they struggled to subsist — the area was gripped by famine — while trying to convert the local inhabitants.

There is one recorded baptism: that of Don Luis’ younger brother. Three of the catechists also made their Jesuit professions while in Ajacán.

Within a few months, Don Luis deserted the Jesuits and betrayed them. Between Feb. 4 and 10, 1571, he led members of his tribe in killing the Jesuits. Only Alonso de Olmos was spared. He lived with his captors for over a year before a Spanish military expedition rescued him (1572). The soldiers killed members of the Chiskiack tribe in retaliation for the massacre of the Jesuits, although Don Luis was never captured.

Spain gave up trying to settle Ajacán, and in the following decades it abandoned most of North America (except for the Florida peninsula), choosing to focus instead on the more lucrative lands of Central and South America.

England then began its advance upon North America, beginning with the failed settlement of Roanoke Island off the coast of present-day North Carolina (1585, 1587), and then successfully at Jamestown (1607).

Clues about the earlier Spanish presence lingered in the territory that England called “Virginia” and circulated among the Jamestown colonists. There is plausible speculation that Don Luis was the same person as Opechancanough, a tribal chief and the brother or cousin of Powhatan, another tribal chief whose daughter, Pocahontas, married John Rolfe of Jamestown. Opechancanough led two attacks against the Jamestown settlers (1622, 1644) before they captured and killed him.

The memory of the eight Jesuit martyrs of Virginia has endured. In 2002, Walter F. Sullivan, the 11th bishop of Richmond (1974–2003), initiated the cause of their canonization. This cause was later transferred to the Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee, which is seeking the canonization of all the martyrs of la Florida.