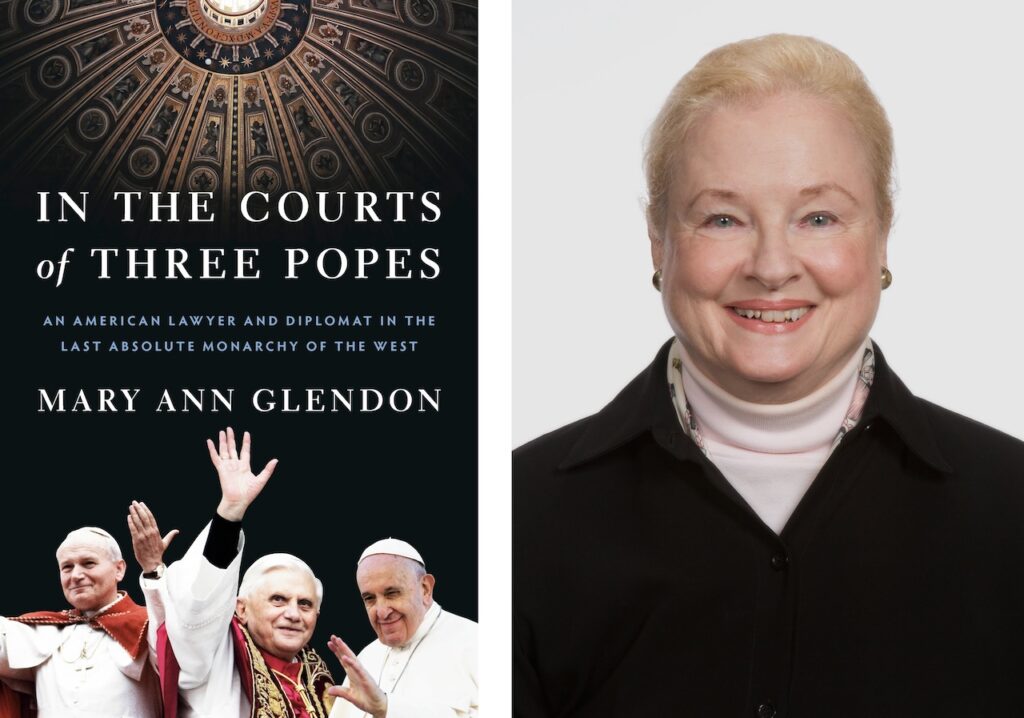

“In the Courts of Three Popes”

Mary Ann Glendon

Image Books, 2024; 219 pages

Mary Ann Glendon’s new book is a welcome addition to the body of narrative nonfiction on the inner-workings of influential but only dimly understood institutions.

“In the Courts of the Three Popes” is a memoir-like examination of Vatican operations, both diplomatic and administrative, from a front-line observer.

Subtitled “An American Lawyer and Diplomat in the Last Absolute Monarchy of the West,” Glendon’s book offers keen insights into how the last three pontiffs handled the more temporal side of church affairs.

Mary Ann Glendon was nominated as U.S. Ambassador to the Holy See in November 2007 and served in that role until early 2009. Although it was but a one-year term, Glendon was already well acquainted with Vatican operations from her previous work as a Holy See representative to the 1995 United Nations-sponsored International Conference on Women in Beijing. She also served as president of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences from 2004 to 2013.

A long-term educator and legal scholar, Glendon today serves as Learned Hand Professor of Law, emerita, at Harvard University. “In the Courts of Three Popes” is Glendon’s 10th book, having published other works of biography, comparative legal traditions, family law and human rights.

Don’t look for exposés or insider gossip within these pages. Instead, Glendon’s book is more a dispassionate discourse on her path to the ambassadorship and on the importance of diplomacy in the Holy See’s interaction with government and cultures the world over.

Glendon is effusive in her admiration for St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI for the theological and spiritual underpinnings that marked their leadership of the universal Catholic Church. What these popes lacked, she observes with sympathy, was an administrative élan that would have greatly assisted long overdue curial reforms.

As the author notes midway through the story, “In terms of the traditional image of the Church as Mater et Magistra, mother and teacher, one might say that when Pope Benedict resigned in 2013, the Vatican was well supplied with doctrinal guidance but in dire need of someone who would take charge of the household.”

Glendon expands on the question of administrative efficiency of the Vatican in her discussion of the Pope Francis pontificate. Although Glendon’s term as U.S. Ambassador to the Holy See ended four years before Francis’ election to the papacy, she kept tabs on the new pope’s administrative style by way of her work as a supervisor at the Institute for the Works of Religion (known commonly as the Vatican Bank) from 2013-2018.

Glendon applauds papal efforts to streamline and improve the Vatican’s administrative and diplomatic efforts but warns against the temptation to bring corporate management techniques into the fray. She also notes that as the church looks to lend its spiritual and moral authority to international relations and policymaking, it should not succumb to charges that it exists only as lobbyist or as “another NGO” (non governmental organization).

Glendon’s book is most effective in discussing the role of the laity in supporting the church’s administrative affairs. She makes effective reference to the Second Vatican Council’s emphasis on lay men and women — not the clergy — to imbue political, economic and social institutions with Christian principles. From that viewpoint, Glendon suggests that while lay Catholics have started exerting more influence within the Curia, there is still room for improvement.

“As is apparent,” Glendon writes, “Holy See officials, whose training has done little to prepare them for administering a sovereign state in the twenty-first century, could certainly benefit from expert lay assistance in many areas. One might even imagine that increased complementarity with laypersons would help to improve morale within the curia.”

Some of the author’s sharpest criticism of the Vatican’s operations centers on its treatment of lay staff as employees and individuals. She notes a reluctance of some long-term Curia workers to welcome and accept lay input, especially, it seems, from women appointees. Even Pope Francis, for all his reforming zeal, seems to come up short in this area.

“One relatively simple way to begin changing curial culture — or at least improve the lives of a few thousand men and women — would be to assure rank-and-file personnel of working conditions in which they can flourish and reach their potential,” Glendon writes. “That would be a major step toward bringing the Vatican’s own practices into conformity with what the Church has consistently proclaimed about the dignity of labor in its long tradition of Catholic social teaching.”

Overcoming “demeaning attitudes and behavior” toward women religious and laywomen employees, who constitute nearly one-quarter of the entire Vatican workforce, would also help improve worker morale, and in turn, presumably, would improve overall operations Curia-wide.

Glendon asserts that the Curia still has a long way to go to realize Pope John Paul II’s vision of “complementarity” between clergy and laith, and between men and women. “Over a quarter-century has passed since [Pope John Paul II’s] 1995 exhortation to ‘all men in the Church to undergo, where necessary, a change of heart and to implement as a demand of their faith, a positive vision of women.'”

Despite these observations however, Glendon remains optimistic that the Vatican can improve its corporate culture and allow lay, religious and ordained staff to bring their talents, enthusiasm and inspiration to the service of the church.

“No one should shy away from service to the Church at any level out of a sense that things are so bad that their efforts would be wasted,” Glendon suggests. She urges laypersons contemplating service to the Church at any level to consider how their energies would fit within the context of one’s baptismal calling to holiness and mission. “That is a matter for each person’s discernment — depending on one’s capabilities, opportunities, inclinations, and personal and occupational responsibilities, and not least on where one is on one’s journey through life.”