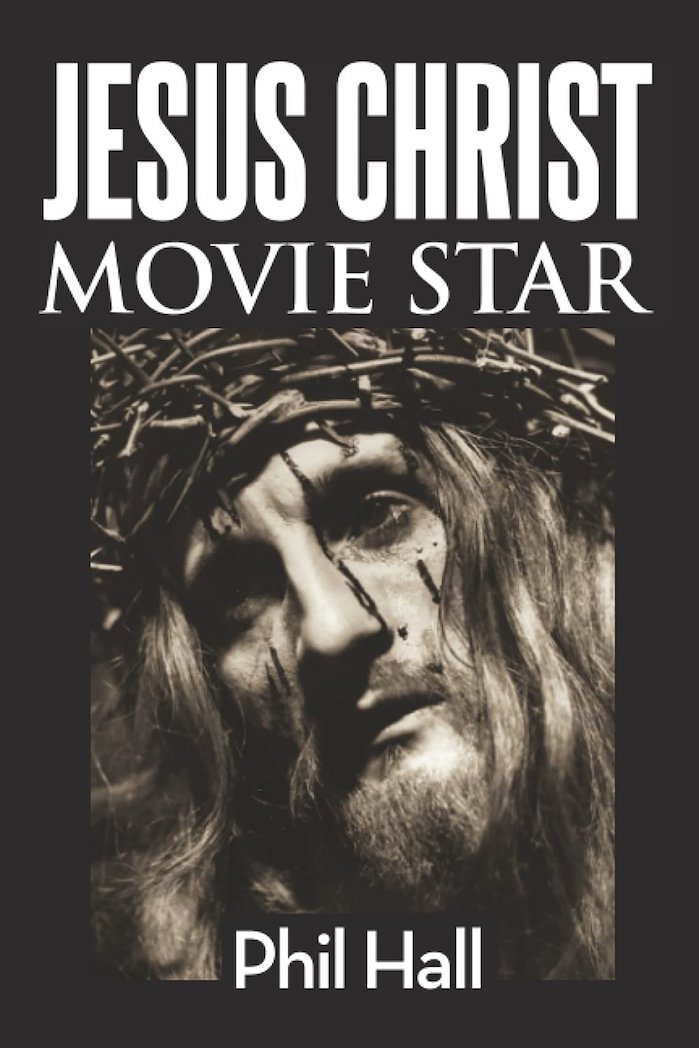

“Jesus Christ Movie Star” by Phil Hall. BearManor Media (Orlando, Florida, 2021). 163 pp., $22.

The life story of Jesus Christ has fascinated filmmakers for more than 100 years. It’s not surprising that more movies have been made about Jesus than about any other subject, but the variation among these portrayals is stunning.

We see the classic, miracle-performing Son of God in epics such as “The Greatest Story Ever Told” (1965) with its all-star cast of Max von Sydow as Jesus and Charlton Heston as John the Baptist. This film achieved success as “an intellectual epic that carefully unfolded the power of Jesus’ ministry,” writes the author of “Jesus Christ Movie Star,” Phil Hall.

At the other end of the spectrum is the snarky microbudget satire, “The Divine Mr. J.,” released in 1974. The universally panned film portrays Jesus as “a cigarette-smoking womanizer who consults with an astrologer and gives in to his mother’s demands to turn water into wine for her personal consumption.” The movie only saw a very brief light of day because it featured 10 minutes of the young Bette Midler as the Virgin Mary, Hall notes.

The host of the celebrated podcast, “The Online Movie Show,” Hall has written many books including “The History of Independent Cinema” and “In Search of Lost Films.” His knowledge of film history, especially that of religious films, is nothing short of encyclopedic.

This highly informative and entertaining tour spans both decades and international locales, starting with cinema’s pioneering days in the late 1890s in France, Bohemia, Australia and the United States. These earliest Jesus-centric films, which Hall calls “gruelingly primitive” by modern standards, were astonishing to audiences of the late 19th century.

The next major advance was the creation of Jesus-centric feature films, starting with 1912’s “From the Manger to the Cross.” Not limited to studio shots, the movie was filmed on location in Palestine (then part of the Ottoman Empire) and Egypt. Showing Mary and Joseph in the flight from Egypt against the backdrop of the Sphinx and the pyramids added striking authenticity, setting a standard for subsequent endeavors.

Hall writes engagingly, giving many interesting details about the films he discusses. We learn that the producers of “From the Manger to the Cross” used local rural people as extras and that to portray the divine infant, they relied on the baby of a traveling Western couple. And at one point, they “found their lives were in danger when Arab locals in Jerusalem objected to the presence of Westerners filming a Christian movie in their ancient city.”

Another strength of the book is its inclusion of film history context. Until the 1960s, Hall writes, “the cinema depiction of Jesus followed a consistent standard: the long-haired, bearded, white-robed figure of Renaissance paintings.” This movie Jesus was “a symbol of piety and respect, with filmmakers and actors working within a clearly defined parameter.”

The 1960s saw a more freewheeling approach, with many films depicting Jesus quite differently from earlier portrayals. Sometimes this new edginess was successful, “while in many films the attempts at irreverence … lapsed into vulgarity or puerility.”

One example from this period is “The Sin of Jesus,” an underground film directed by Robert Frank and released in 1961. Here Jesus is beardless, sports short hair and wears contemporary clothing. He’s not particularly pastoral and seems to lack the ability to connect emotionally.

Much more controversial was “Parable,” which was shown at the 1964-65 World’s Fair in New York. Here Jesus wore a clown’s costume and makeup, “a wild artistic leap” that nearly prevented the film from screening.

A 1979 film that was also controversial, albeit briefly, is Monty Python’s “Life of Brian.” It had a large impact on popular culture, though Jesus only appears in two scenes, as an infant and then as an adult giving the Sermon on the Mount. In the latter, he’s so far away from the crowd that he is mistakenly thought to be saying, “Blessed are the cheesemakers.”

Still, the film doesn’t really aim its “comic wrath” at Jesus, but rather, “at the social extremes of Roman-occupied Judea,” according to Hall. “The local population has a surplus of political militants who use the vaguest suggestion of religious zealotry to excuse their violently antisocial behavior, while the Roman aristocracy are presented as clueless and dimwitted hedonists who uphold their reign with casual cruelty.”

Ultimately, “Life of Brian” was quite successful at the box office and paved the way for future films that “veered closer to the profane than the sacred.”

In the 21st century, “among the most eccentric Jesus-centric films ever made” is Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” (2004), which told the story of Jesus’ final hours in harshly explicit realism. Jewish leaders’ charges of antisemitism only seemed to enhance interest in the film, which cost $30 million to make and grossed $612 million.

The 21st century also saw much more diverse Jesuses, such as actor Aviv Alush’s portrayal of him as a Middle Eastern man in “The Shack” (2017). (Also here, Octavia Spencer is cast as God the Father.)

These are only a handful of the myriad films that Hall covers. He describes his book as “a culmination of two very different passions in my life: the celebration of all things cinematic and my Christian faith.” Anyone interested in film history — especially religious cinema — will find it hard to put down.

Roberts is a journalism professor at the State University of New York at Albany who has written/coedited two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.