UPDATE: A previous version of this article erroneously stated that the Shroud of Turin Exhibit will travel to Christ the King, Abingdon, Sept. 6. While Dr. Cheryl White will be giving a presentation on historic and scientific studies of the shroud at Christ the King Sept. 6 at 7 p.m., the Shroud of Turin Exhibit and artwork will not be present at Christ the King.

The face on the Shroud of Turin has been astonishing Christians for centuries. At the Shroud of Turin Exhibit during the National Eucharistic Congress July 17-21 in Indianapolis, Bishop Barry C. Knestout was among them.

“This is something else,” said the bishop, marveling at a three-dimensional hologram of the famous photographic negative of the shroud.

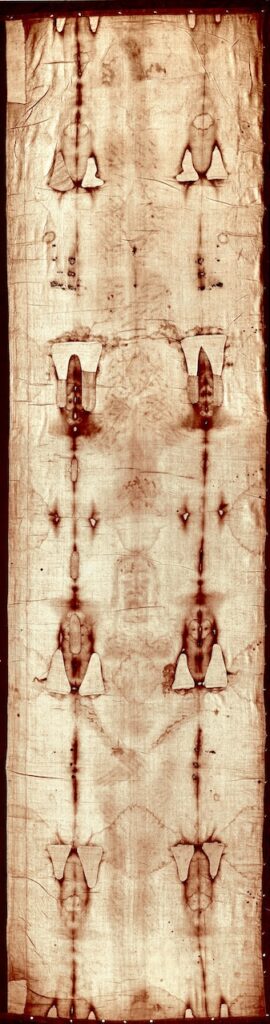

The exhibit included a replica of the shroud, artwork based on the shroud, a presentation by historian Dr. Cheryl White, information about the physicality of crucifixion, a sculpture based on the dimensions of the figure on the shroud, and a hologram that brought the face to life.

“You look at this, and you say, ‘Wow. What else could produce that?’” said Bishop Knestout.

The Catholic Church takes no official position on the authenticity of the shroud, instead declaring it an artifact worthy of devotion because it viscerally depicts the story of Christ’s passion. St. John Paul II called it “a mirror of the Gospel”; Pope Francis has called it “an icon of love.”

The shroud depicts a man scourged, crowned with thorns, and crucified through the feet and the wrists. There is a post-mortem wound on his side, and wounds in his knees from multiple hard falls. There are no broken bones, but the cartilage in the nose is broken.

There are no brushstrokes on the shroud; instead, the fibers of the cloth were themselves darkened, as though they were exposed to light. Some researchers have posited that the image was taken using a primitive form of photography. Others say that the image was created during the Resurrection, but there is no scientific way to test this hypothesis.

“Every time we answer a question about the shroud, we have another question, and we are led further and further into a mystery,” said White. “We can know what is physical and observe what is true using the historical and scientific method. But we cannot answer the most important question: How was the image formed?”

In 1988, a team of scientists tested the age of the shroud using carbon dating. Three laboratories found with 95% confidence that the shroud was produced between 1260 and 1390. This corresponds to its appearance in Lirey, France, in 1353.

However, the carbon-dating tests have been disputed. The shroud was damaged and repaired many times, was stored and handled in conditions rife with bacteria and candle smoke, and once caught on fire. These circumstances have led some of the faithful – and many scientists – to question the accuracy of the tests.

As with all relics, the position of the Vatican is to direct the faithful not towards the artifact itself, but towards what it tells us about Christ.

“As Christians, in the light of the Scriptures, we contemplate in this cloth the icon of the Lord Jesus crucified, dead and risen again,” wrote Pope Francis in 2020. “To He we entrust ourselves, in Him we confide.”

The presentation given by White, however, demonstrated that a burial cloth depicting a mysterious image of Christ has been venerated by Christians since the Apostolic Age.

As recorded by St. Athanasius, an “image of Our Lord” was taken from Jerusalem to Syria in 68, two years before the sack of Jerusalem by Titus and Vespasian. Later, an image of Christ “not made by human hands” was transferred to Constantinople from Edessa, in upper Mesopotamia, in 944, and installed at a church in the Byzantine capitol.

That same image was later counted in a relic inventory taken by the Byzantine emperor in 1201 and was seen by Robert de Clari, a French knight on crusade.

De Clari wrote in his account of the 1204 sack of Constantinople, “There was the shroud in which Our Lord had been wrapped, which every Friday was raised upright, so one could see the figure of Our Lord on it. No one, either Latin or Greek, knew what became of it when that city fell.”

White suggested that the subsequent disappearance of the burial cloth from the historical record may have been due to fear of punishment by Church officials, who were outraged that the Crusaders had looted the Eastern Roman capitol en route to the Holy Land.

“The pope who called for the Fourth Crusade, Pope Innocent III, was furious when he learned that Christian armies had sacked the city of Constantinople and committed what he called ‘unspeakable and blasphemous acts of looting, burning and pillaging,’” said White. “And he issued mass writs of excommunication.”

“If you had in your possession one of the most sacred relics in Christendom, and you’re living in this environment of excommunication, are you going to tell anyone?” said White.

White discussed another scientific study of the shroud: There is pollen on the artifact that places it in Jerusalem, Antioch, Edessa, and Constantinople at some point in history.

“Considering the scientific evidence, the shroud has been at every one of those places. And I guarantee you, this evidence would convict you in a court of law,” said White.

Bill Lauto, an environmental scientist who converted to Catholicism after studying the shroud, also gave a talk at the exhibit. He discussed other remarkable aspects of the shroud, including the bodily fluid found around the spear wound, and the fingerprints found on the feet.

Using the image on the shroud, Lauto painted a picture of the crucifixion.

“With the weight [of the crossbeam] on his back, falling straight to the ground three times, he probably developed a tear in his aorta,” said Lauto. “The wounds on the shoulder all match carrying that beam.”

“From the wound in his side, we can say it was made with a Roman short spear, not the long one,” said Lauto. “Using a short spear tells us the cross was no more than 6 feet tall, which means he was naked, on the cross, in front of everybody.”

Nine-inch iron nails, a Roman short spear, and a crown of thorns – all consistent with the wounds of the figure on the shroud – were on display.

A replica of the Sudarium of Oviedo, thought to be the cloth that wrapped Jesus’ head, was also on display. Housed in Spain since 616, stains on the sudarium perfectly match the nose, cheekbones, and thorns on the shroud.

Bloodstains on both the shroud and the sudarium are AB blood – the same blood type found in the Eucharistic miracle at Lanciano, the Eucharistic miracle in Bolsena-Orvieto, and reported Eucharistic miracles in Buenos Aires.

Like St. John Paul II and Pope Francis, Bishop Knestout was less concerned with the historical and scientific debate than by what Christ crucified means for our faith.

“AB blood is the universal recipient,” said the bishop. “Initially, you might think the blood of Christ would be a universal donor. But he takes on the sins of the world; he receives them onto his blood.”

On September 6, White will give a presentation on historic and scientific studies of the shroud at visit Christ the King, Abingdon, at 7 p.m.

“We’re going to try and invite the parishes in the deanery, and even non-Catholic Christians in Abingdon,” said Father Chris Masla, administrator of Christ the King, Abingdon, and St. John, Marion. “The church is on Main Street, and we believe this is an important topic and a great tool for evangelization.”