When a committee formed in 2016 at the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, Richmond, to restore the century-old gallery organ, Carey Bliley had no idea the process would take eight years and more than $3 million.

“We started off looking to restore what we had,” said Bliley, chair of the organ committee at the cathedral. “We brought three different restoration specialists in, and all three of them came back and said, ‘There’s nothing to restore.’”

Eventually, after a journey through Europe and across America to listen to different instruments – as well as feedback from parishioners – the committee decided to replace the old organ with a new mechanical-action organ built by Juget-Sinclair, a Montréal-based organ building company.

Juget-Sinclair built two smaller organs for the cathedral, and the gallery organ, called Opus 55, was installed onsite by company craftsmen beginning April 2. Now, the massive instrument has been fully installed, but Juget-Sinclair technicians remain onsite, tuning and voicing the pipes.

“The cathedral committee was looking for a mechanical-action organ, also called a tracker-action organ, which means that when you play, you actually move mechanical pieces. There’s no electricity between the player and the pipes,” explained Robin Côté, president of Juget-Sinclair.

“On a mechanical-action organ, the player really feels the wind,” Côté added. “Musically, it’s very satisfying when you play that kind of organ, because you really feel the relationship the wind has with the instrument.”

“This is how organs were built in the 16-, 17-, and 18-hundreds, [instruments] that are still playing today,” said Bliley.

Through July, Côté and the Juget-Sinclair team will be tinkering with pipes, listening to different sounds at different spots in the cathedral, and suiting the instrument to its acoustics.

On Tuesday, Oct. 29, Bishop Barry C. Knestout will lead Vespers (Evening Prayer) and dedicate the instrument. Olivier Latry, titular organist at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, will perform a concert the following evening, Oct. 30.

Tailoring the instrument

The process of voicing the organ is just that, said Côté: giving the organ its voice.

“People from the South have a different accent than people from Canada,” said Côté, who speaks with a French-Canadian accent. “Some of us have a different way to achieve a sound. The way we voice the organ is very important.”

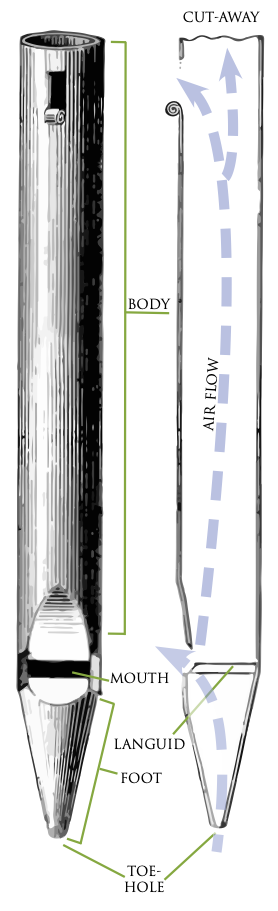

An organ pipe is divided into two essential parts: the foot and the body.

When a key is played, air enters the bottom of the foot through the toe-hole. The air then encounters a languid and enters the body of the pipe through the windway.

The air is shaped into a sheet of wind by the body of the pipe, and most of the sound comes from the force of wind traveling through the mouth of the pipe. The length of the pipe determines the pitch of the note; the longer the pipe, the lower the sound, as the sound waves elongate.

The languid, which divides the foot from the body of the pipe, influences the tone of the sound, said Juget-Sinclair technician Alex Ross.

If the languid is higher on the pipe, there are more harmonics, and the sound is brighter. If the languid is lower, the harmonics are reduced, and the sound is darker.

“Some stops are designed to have a brighter sound, and others to have a darker sound,” said Ross. “If we tap the languid too high, we can tap it back down.”

The volume of the pipe is controlled by the size of the hole at the bottom of the foot. Technicians can adjust the size of the hole with a hammer.

The windway is adjusted with a knife, which is a trickier task: The metal cannot be put back, so the change is permanent.

The Opus 55 gallery organ has 4,336 pipes. Laid end-to-end, the length of the pipes adds up to over two miles.

“It’s sort of like tailoring a suit,” said Ross. “First, we came and took measurements of the church, then we built the organ, leaving a bit of extra material. Then we brought it to the church for the ‘first fitting,’ and now we’re doing the tailoring to get it to fit perfectly to the sound of the room.”

Centuries of knowledge

The pipes aren’t the only example of old-world craftsmanship found on Opus 55. Almost everything, from the keyboard to the wooden molding, was made by hand in the Juget-Sinclair shop.

“We keep outsourcing to the minimum,” said Côté.

Each of the 67 stops were made from oven-baked porcelain, not plastic; the markings on each stop were engraved, not stamped with ink. The body of the organ itself is made of solid wood.

“We put a lot of care into that kind of thing,” said Côté. “It’s not just a veneer with plywood – no. This is our philosophy, our way of thinking.”

Daniel Sáñez, director of music and liturgy and principal organist at the cathedral, pointed out a particular detail. “The trees they use are from the center of the forest where there’s less wind,” he said. “If the trees sway from wind and storms, the grain won’t be as straight.”

Organ-building industry knowledge has been imparted from one generation to the next for centuries.

“There’s no school for it,” said Ross. “A furniture-maker knows how to build a chair because he’s seen so many chairs, and experimented building his own chairs, that he can just kind of do it. It’s the same sort of thing, but on a much bigger scale.”

“In organ building, you learn from tradition,” said Côté. “The guy who taught you how to do it learned from an older builder, who brought the tradition with him. It evolves slowly, slowly. There is no school [for building organs] in North America.”

Bliley and Sáñez, who is also on the committee, said they were impressed not only with the culture of Juget-Sinclair, but by their information-based approach to securing the contract, which is expected to land at $3.2 million after all work is complete.

“You can always tell when someone’s trying to sell you something and when someone is authentic and real,” said Bliley. “You could tell from the beginning that Robin and [vice president] Stephen [Sinclair] were the real deal.”

“They just said, ‘This is what we do – you might like it, you might not like it, here are some of our instruments, go see them. If you like them, call us,’” said Sáñez.

‘A beautiful creation’

Sáñez said he hopes the organ will someday be considered “a landmark within a landmark” in downtown Richmond.

“I’ve played the oldest organ in the world, in Switzerland; I’ve played the organ at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig; I’ve taken lessons at the church of J.S. Bach, and I’ve played the organs he played,” said Sáñez. “This organ is a beautiful creation. It’s very unique. It’s very special. And if I didn’t think so, I wouldn’t say that.”

“When one is playing, it feels like you’re having a deep conversation with somebody very old, somebody’s who’s got lots of wisdom,” said Sáñez. “You’re at the feet of a masterful being, and they’re communicating with you. You’re not just playing the instrument. It’s an interaction; the instrument plays you, too.”

Ultimately, the hope is that Sáñez will be just one of many players over the centuries to play Opus 55.

“This organ project isn’t really for us,” said Bliley. “It’s for future generations. It’s built to last.”