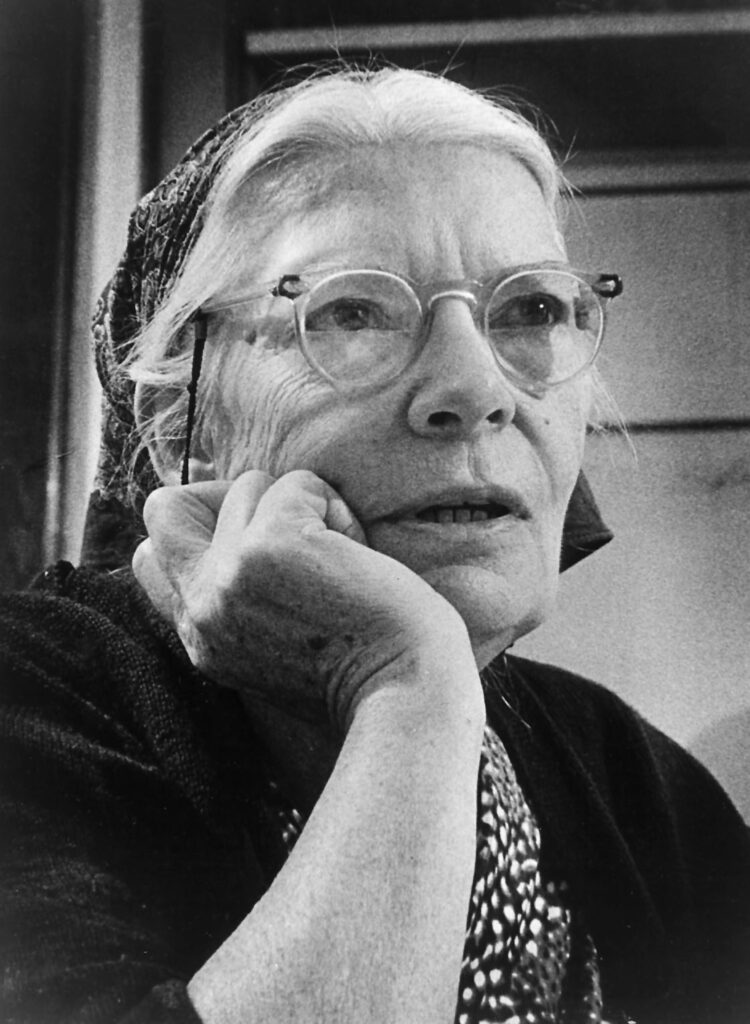

WASHINGTON — The sainthood cause for Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, believes it could have all of the documentation prepared at some point next year to send to the Vatican Congregation for Saints’ Causes.

It would represent the culmination of an effort begun informally in 1997, but in earnest in 2002. After that, the process is largely in the Vatican’s hands — but also in God’s.

Robert Ellsberg, publisher of Orbis Books, a ministry of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, said the Claretian Fathers, through their magazines U.S. Catholic and Salt, began hailing Day as a saint shortly after her death in 1980.

Ellsberg had included Day in his book “All Saints,” and he had given a talk shortly after its 1997 publication, which argued that she should be canonized. Cardinal John O’Connor of New York, who voiced opinions on Day’s canonization in the 1980s, invited Ellsberg and his family to attend a Mass he was celebrating to observe the centenary of Day’s birth.

After the Mass, according to Ellsberg, Cardinal O’Connor approached him and asked whether he really thought Day should be made a saint. When Ellsberg said yes, the cardinal asked him to gather some others who knew Day for a conversation with him.

“He really wanted to hear what people had to say. He didn’t act like, ‘What a big favor I’m doing for Dorothy Day,’ Ellsberg told Catholic News Service. “He said, ‘I do not want it on my conscience that I did not do what God wanted done.’”

Day, even prior to helping start the Catholic Worker, had led a varied life. Carolyn Zablotny, editor of the Dorothy Day Guild’s newsletter, linked Day’s time to the present because Day served as a nurse during the flu pandemic of 1918-19. Day was also a suffragette and a journalist. She had an abortion and was so distraught about the experience that she tried twice to kill herself.

Upon establishing the Catholic Worker in 1934, Day found a place not only for her pacifist views — opposing U.S. entry into World War II and Vietnam — but also for direct action to aid the poor and workers. (Pope Pius XII declared May 1 the feast of St. Joseph the Worker in 1955.)

Zablotny, whose only contact with Day was on the receiving end of a phone call, said the Catholicism of her youth was “an intellectual thing. … We memorized the faith, right?” But in her college days in the 1960s, with “the ferment of social action and cries for justice,” something more seemed needed.

Her school, Manhattanville College, “had every Catholic periodical you could imagine. But they got the Catholic Worker, the newspaper. It wasn’t glossy, and it wasn’t a good size. They put it on top (of the shelves), and you needed a little round stool to get to it,” Zablotny said.

“When I was in high school, I remember my older sister bringing my mother as a gift, (Day’s autobiography) ‘The Long Loneliness.’ And my mother loved it. There must have been a nun who was hip and turned my sister on to that book, I experienced their excitement. I read ‘The Long Loneliness,’ but it was beyond me in high school. … You had to read between the lines. But in college, I realized ‘That’s that!’, and I knew the autobiography grabbed me as a teenager with its provocative title.”

“My life was changed when I met her a few times,” said David O’Brien, a retired Church historian at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. “Many of my students became lifelong Catholic Workers.”

O’Brien wrote Day’s obituary in Commonweal magazine, calling her “the most interesting and influential” American Catholic of her time. “She did not live apart from life, like (Trappist monk, and Day contemporary Thomas) Merton, but she lived right in the heart of the city and right in the heart of the great issues of the day,” he told CNS.

“Nonviolence has moved from the edge to the center of Christian teaching,” O’Brien said. “There’s a reversal of Catholic teaching, and Dorothy Day’s original pacifism was pretty courageous, because there were not Catholics of any significance” advocating that.

George Horton, vice postulator of the cause, is doing his work for no pay. Zablotny, his wife, edits the Dorothy Day Guild’s newsletter, and the cause’s only employee, Jeff Korgen, works part time with help from the Ignatian Volunteer Corps and some Archdiocese of New York staff. “Maybe I’m good at delegating,” he chuckled.

Advancing a sainthood cause does not come cheap; most efforts easily run into six figures and sometimes seven — a bit of a conundrum when the object of the cause embraced voluntary poverty. “We’re not like a religious order trying to get their founder canonized. They can draw on the finances of the order, both provisional and staff. We’re not like that. The legacy of Dorothy Day is the Catholic Worker movement, and the people in the Catholic Worker are out feeding the poor, healing the homeless, demonstrating for justice and peace; they’re true to the voluntary poverty Dorothy practiced,” Horton said.

Korgen, whose title is “director of the inquiry,” had been director of development and planning for the Diocese of Metuchen, New Jersey. In his work, he combines his training in both canon law and his prior career in social ministry.

The Vatican has an exacting process for how documents for a sainthood cause are to be prepared. With the help of 50 volunteers who are transcribing every word Day uttered or published, the work is getting done. Korgen estimates it could run up to 30,000 pages once it is completed.

He wouldn’t say if he found any surprises about Day, but Korgen did take exception to characterization of her pre-Catholic Worker life as “bohemian.”

“Bohemian, bohemian, bohemian. You think about any young adult living in New York City in their 20s. Maybe in their 20s they weren’t talking about big ideas, but she was hanging out with journalists and radicals and talking about making a better world,” Korgen said. “It doesn’t seem to me her lifestyle was all that out of sync with what people today in their 20s do now.”

However, “we see the signs of what she became in her young adult life,” Korgen added. “She would finish one of those long nights drinking with a trip to one of the parishes in Greenwich Village.” After becoming pregnant by her common-law husband, Forster Batterham, she wanted to get married, but he refused.

“He was the love of her life, but he was as stubborn as she was,” Korgen said. “‘We have to get married,’ ‘It’s against my principles.’” Batterham’s next paramour became incurably ill, and he called Day asking for her help. And she complied.

“This is the woman who got her man, and she’s taking care of her like, ‘Yeah, this is what I do.’ Many of us who have had romantic relationships in our lives. We would say, ‘That’s heroic virtue right there. That’s the making of a saint.”

Ellsberg said Day’s abortion should not disqualify her for sainthood.

“That gives the idea that abortion is a category of its own and is going to burn in hell forever. That is not the way to represent a Catholic understanding or Christian understanding of sin and salvation. Traditionally, we teach that there is no sin that cannot be forgiven. There is nothing we can do that separates us from the love of God if we turn to him with contrite hearts,” he said.

By the same token, though, it would be wrong to consider Day the patron saint of women who have undergone an abortion, thereby minimizing her contributions to Church and society.

“That’s like saying St. Paul should be the patron saint of murderers. St. Augustine should be patron of those who are promiscuous,” he said, adding such a move would be “superficial.”

Another contradiction is the oft-repeated quote of Day: “Don’t make me out to be a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.”

Zablotny said it is a warning against others “abdicating” their call to Christian charity. “She didn’t want people put on a pedestal. Therefore, the works of mercy — Oh, Dorothy can do that, she’s a saint,’ which gets the rest of us off the hook. One of the key insights of Vatican II … is that we’re all called to be saints,” she said.