WASHINGTON – Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson was sworn in as a Supreme Court justice June 30, becoming the first Black woman in that role.

The ceremony took place at the Supreme Court, after the court finished issuing its final opinions of the 2021-2022 term and Justice Stephen Breyer’s retirement was official.

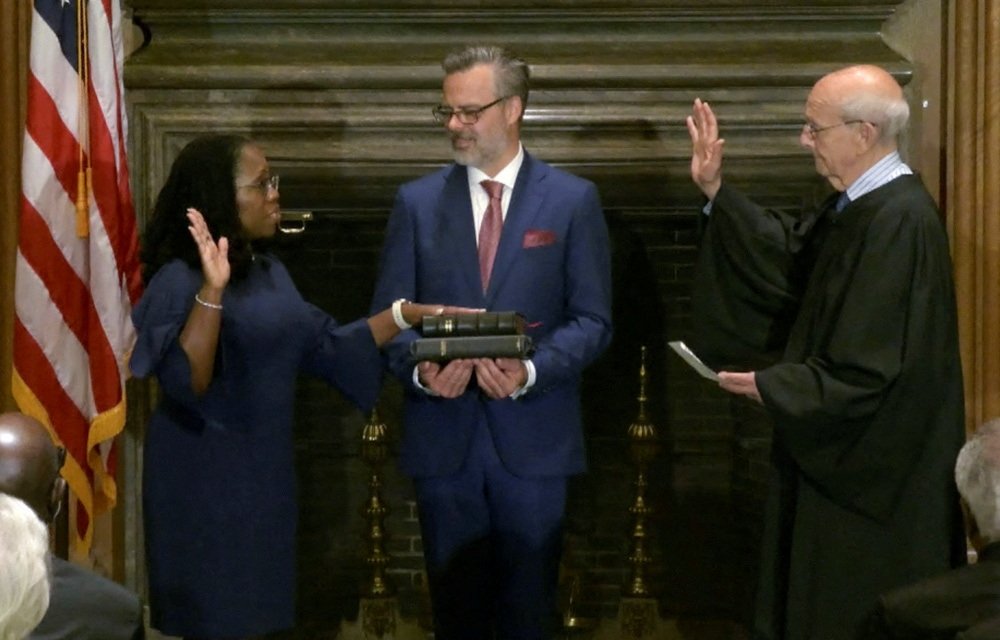

Jackson took the constitutional oath, administered by Chief Justice John Roberts and a judicial oath, administered by by the newly retired Breyer.

“With a full heart, I accept the solemn responsibility of supporting and defending the Constitution of the United States and administering justice without fear or favor, so help me God,” she said.

“I am truly grateful to be part of the promise of our great nation,” she added.

Jackson, in the presence of other justices and retired Justice Anthony Kennedy, took the oaths with her hand on two Bibles held by her husband, Patrick: a family Bible, and a Bible described as the “Harlan” Bible, that Justice John Marshall Harlan gave to the court in 1906.

In a statement, Jackson, 51, thanked both Roberts and Breyer and said Breyer had been her “personal friend and mentor” for two decades.

Breyer, also in a statement, issued by the court, said he was “glad today for Ketanji.”

“Her hard work, integrity and intelligence have earned her a place on this court. I am glad for my fellow justices. They gain a colleague who is empathetic, thoughtful and collegial,” he stated. “I am glad for America.”

Breyer also said his replacement would “interpret the law wisely and fairly, helping that law to work better for the American people, whom it serves.”

Jackson was confirmed by the Senate April 7 in a 53-47 vote.

Like the Senate, advocacy groups had a mixed reaction to her confirmation vote.

“Judge Jackson’s work as a public defender and a civil rights lawyer provide her a necessary framework” to serve on the court, said Mary Novak, executive director of Network, a Catholic social justice lobby.

She said her organization and its supporters are confident Jackson will “bring our country a step closer to achieving a more representative, inclusive and just democracy.”

Conversely, Jeanne Mancini, president of the March for Life Education and Defense Fund, said her organization was disappointed with the vote.

“Jackson’s record of judicial activism fails to align with the role of a Supreme Court justice, which is to interpret the Constitution without prejudice and to apply the law in an unbiased manner,” she said.

In a statement issued two months before the court voted to overturn its Roe v. Wade decision, she said: “Pro-life Americans understand the dangers of judicial activism, and the threats it poses to women and their children.”

During Jackson’s confirmation hearings this March, Republican senators said she was soft on crime and had not revealed her judicial philosophy, while Democrats emphasized Jackson’s qualifications for the role and the historic opportunity of confirming the nomination of the first Black woman to the Supreme Court.

Jackson was a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, after serving nearly eight years as a federal trial court judge in Washington. She worked with law firms and served as a federal public defender.

She clerked for Breyer in the 1999-2000 court term and said during remarks announcing her nomination that he demonstrated how a Supreme Court justice can demonstrate civility, grace and generosity of spirit.

During her confirmation hearing, Jackson said it was “extremely humbling” to be considered for Breyer’s seat on the court and added that she “could never fill his shoes,” but if she were confirmed, she hoped she would “carry on his spirit.”

Court watchers have pointed out that although her appointment is historic, her spot on the bench will not change the court’s current balance of liberal and conservative justices.

Jackson was asked a few times in the confirmation hearings about her abortion views. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., asked Jackson, as she has asked the last three court nominees, if Roe v. Wade was settled law. Jackson, as other nominees before her have done, agreed the court’s decision was a binding precedent.

When she was asked by Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., about her faith, she responded that she is “Protestant, nondenominational.” When pressed further about how important her faith is to her, she said that it was very important but added: “There is no religious test in the Constitution under Article 6.”

She also said it’s very important to “set aside one’s personal views about things” in the role of a judge.

When she was announced as Biden’s court nominee Feb. 25, Jackson said she was “truly humbled by the extraordinary honor of this nomination” and thanked God for bringing her to this point in her professional journey, adding: “One can only come this far by faith.”

She said she hoped her love of this country and the Constitution would inspire future generations of Americans.

Jackson will join a bench that includes six Catholic justices – Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Amy Coney Barrett, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Sonia Sotomayor. Justice Neil Gorsuch was raised Catholic but is now Episcopalian and Justice Elena Kagan is Jewish.