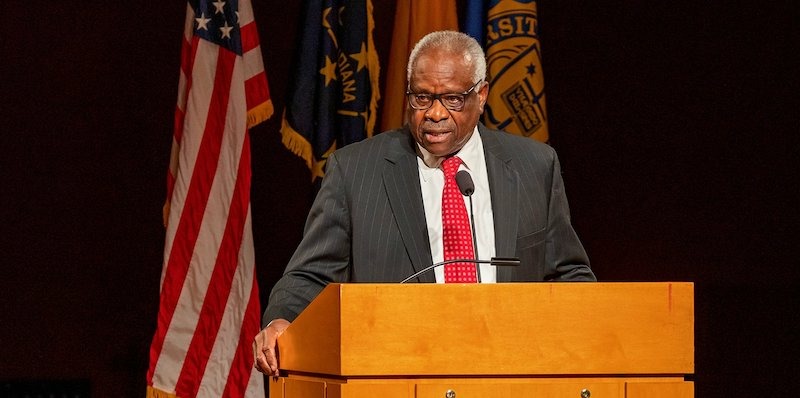

SOUTH BEND, Ind. — In an address at the University of Notre Dame Sept. 16, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas spoke about being personally grounded by his Catholic faith — which he said he “ran away from” when he was young and “crawled back” to 25 years later.

He also spoke more broadly about how the country in previous decades had been more rooted in the values of the Declaration of Independence and demonstrated a sense of patriotism and overall unity that is less prevalent today.

“We have failed the Declaration of Independence, but it has not failed us. It endures because it articulates truth,” he told a crowd of about 800 people attending the 2021 Tocqueville Lecture for Notre Dame’s new Center for Citizenship and Constitutional Government.

Thomas, who was nominated to the Supreme Court in 1991 by President George H.W. Bush, stressed this document — signed by the Founding Fathers with its emphasis that all are created equally — has “weathered every storm” and still has something to say today.

He also said he has seen signs the values inspired in this text still hold true, something he observed firsthand this summer when he and his wife, Ginni, spent three weeks traveling across the country in their RV.

“There is something true, something transcendent, something solid, something that pulls us together rather than divides us,” Thomas said, referring to campground conversations he had with people, before they recognized him, and the proud American flag displays he and his wife noticed.

At the start of his one-hour talk, Thomas, who is known for being quiet on the bench, joked that he should quit while he was ahead after receiving a long round of applause just after a student introduced him.

He acknowledged that he hasn’t been one for public speeches, noting his former colleague Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in 2016, encouraged him on this path, but he admitted Scalia was “more of an extrovert than I am.”

Thomas spoke about growing up in Georgia in the ‘50s and ‘60s as being in a different world where there was a “deep abiding love for the country.”

Throughout his remarks, he referred to this loss of patriotism, which he said has been replaced by a more cynical view. He also bemoaned that current climate puts more of an emphasis on differences and divisions.

He said he learned from his grandparents and the sisters who taught him at St. Benedict the Moor School in Savannah, Georgia, how to “navigate through and survive the negativity of the segregated world without negating the good that there was.”

To this day, “I revere, admire and love my nuns. They were devout, courageous and principled women,” he said of the Franciscan sisters who ran the school from its start in the early 1900s until it closed in 1970.

He said that even though he was in the segregated South, the sisters emphasized that all were equal in God’s eyes. As a young man, he said, he was less focused on rights than on what was required of him and had “no room for self-pity.”

This assurance left him when he was 19, following the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He left the seminary where he was studying, saying: “I lost faith in the teachings of my youth” and “thought my country and my God had abandoned me.”

At that point, he said he was “consumed by negativity, cynicism, animus and any other negative emotion that you could conjure up. Sadly, the destructive disposition that I exhibited then appears to be celebrated today.”

What had once given his life meaning and a sense of belonging was suddenly seen as old-fashioned and antiquated.

As a college student, he said he rejected his faith, family and country and “filled that void with victimhood — a Black man with an ax to grind” focused on racial differences and grievances, which he once again likened to current responses.

In 1970, after returning to his campus at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, after a riot, his view changed. He said he stood outside the chapel and asked God to “take hate out of my heart” and began what he described as a return to familiar ground.

In a quiet moment at the end of his Notre Dame speech, a few students in the auditorium chanted, “I still believe in Anita Hill,” which was followed by boos from the crowd, the students being escorted out, and then applause. Hill, who worked for him from 1982-83, accused him of sexual harassment during his 1991 confirmation hearing.

In a question-and-answer session following his talk, Thomas was asked about life on the nation’s high court.

When asked whether the attorneys’ oral argument ever change his mind, Thomas said, “almost never,” stressing that the “real work is in the briefs.”

The justice praised Notre Dame’s law school noting that many of his clerks attended it as did his colleague on the bench now, Justice Amy Coney Barrett. He said he would have gone there too if he had visited the university when he was applying.

Thomas bemoaned that too often people think the justices make policy, which he said the media and interest groups promote and this concerns him because he thinks it could “jeopardize faith in the judiciary.”

He said his Catholic faith does not conflict with judicial opinions and that his favorite prayer, one which hangs on the wall of his office, is the Litany of Humility.

“Having been humbled, I have every reason to be humble,” he told the students and faculty members before adding advice: “I think you start with that, and being true, being honest with yourself about what you know (and) what you don’t know. Also, do not lose sight of the good in people.”

Follow Zimmermann on Twitter: @carolmaczim