NEW ORLEANS – We all know Rome wasn’t built in a day, but LEGO architect Rocco Buttliere had three months, which definitely gave him a running start over Julius Caesar.

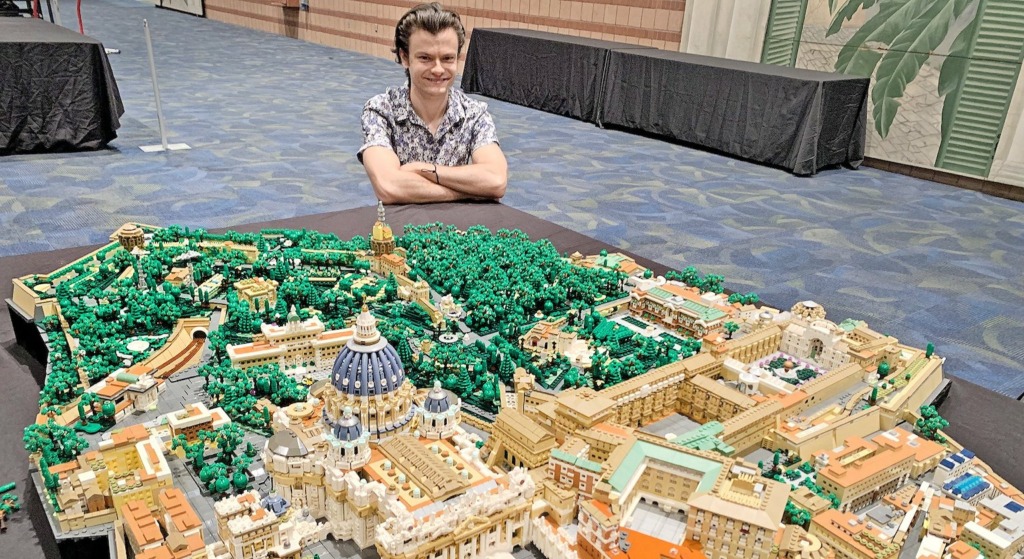

Working quietly in his Chicago-area home during the lull of the pandemic in 2020, Buttliere cobbled together 67,000 tiny, plastic LEGO pieces to create an improbably realistic 3D replica of Vatican City State.

The 1:650 scale model is so faithful to the cobblestones shaded by Bernini’s colonnade that it even includes a tiny red tile marking the top-floor window of the Apostolic Palace from which Pope Francis recites the Angelus each Sunday.

For a kid who began playing with his two older brothers’ LEGO sets as child and who even brought his LEGOs to college while pursuing a degree in architecture, those 800 hours he spent last year were the cornerstones of one his greatest artistic achievements.

“What inspired me was just the fact that there’s almost 4,000 years of human history represented in the architecture and the museums and the artifacts themselves,” said Buttliere, 26.

His LEGO artwork of Vatican City State and another of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge were two of the major attractions at BrickUniverse, a multicity LEGO exhibition that came to the New Orleans area Aug. 14-15.

“That level of spiritual resonance was something that really made me want to tackle the whole (city state),” he told the Clarion Herald, newspaper of the Archdiocese of New Orleans.

Since he began tinkering with LEGO sets – taking apart the sets and using loose bricks to craft his own works – Buttliere has created more than 60 different models and managed to make a full-time living based on traveling exhibitions and commissions.

He was nearing completion on his most ambitious work yet – a 1:650 model of first-century Jerusalem – for a museum in Brazil. That work is composed of 114,000 pieces and has taken eight months.

“I started on New Year’s Eve 2020 and have one box left to ship to them,” Buttliere said. “That’s like the project will never end. But I’m so grateful to have clients like that who will pay me to do what I love.”

The most challenging aspect of the Vatican piece was figuring out how to create the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, Buttliere said. His knowledge of everything LEGO drew his mind to a box of rare, sandstone blue dinosaur tails, which he expertly repurposed into the dome’s shell.

“That really got the ball rolling,” he said. “Those dinosaur tails have come in so many different colors over the years, and blue is the one that’s trickier to track down.”

Buttliere visited Rome only once – there was a LEGO convention in the Eternal City – and spent only a half-day walking through the basilica and Vatican museums. He spent much of his time sitting inside the Sistine Chapel (although Michelangelo’s interior frescoes can’t be seen on his piece even if someone were to peel off the roof).

He tackles a huge project in sections, starting with the most challenging, in this case the basilica. He relies on 3D images from Google Earth and then lays out the landscapes in AutoCAD, a design software, to draw construction lines.

“The medieval walls kind of follow an irregular pattern, and then you are kind of going uphill as you move toward the back of the landscape,” he said. “The colonnade is an oval, and LEGO likes to fit squares really well, so anything with curvature is going to be inherently challenging. In this case, it uses a combination of those square and circular parts to get the curvature of the ‘ovato tondo.'”

Of the 67,000 pieces in the Vatican work, about 1,300 are “unique” pieces, meaning they are rarer and are included only in certain LEGO sets.

“If you buy a LEGO set off the shelf, even the largest ones tend to only have 100 to 150 unique elements in them,” Buttliere said. “In terms of my own work, Vatican City is the most differentiated and stylized, but that makes sense when you consider that it represents a landscape that has different buildings from over the millennia.”

For ease of travel, the Vatican piece can be subdivided into 13 subsections. The only collateral damage of the most recent trip to New Orleans were a few broken tree branches in the papal gardens.

“But I always bring some replacements for fragile things like that,” Buttliere said. “Everything except the trees are glued.”

Since his models are built basically to the same scale, Buttliere said a little-known fact becomes readily apparent: “You could fit the entire country of Vatican City underneath the mid-span of the Golden Gate Bridge.”

That would not have pleased Caesar.