RECONFIGURATION

NORTHERN VIRGINIA BECOMES A DIOCESE

The Diocese of Richmond has always been geographically expansive. Originally, its territory was the entire Commonwealth of Virginia, which reached from the Atlantic Ocean to the Ohio River (1820). The territory of the diocese was reconfigured several times (1850, 1868, 1974).

On August 13, 1974, several territorial changes took effect simultaneously. The ecclesiastical boundaries of the Dioceses of Richmond and Wheeling (soon to be renamed Wheeling-Charleston) were aligned with the civil boundaries of Virginia and West Virginia, respectively.

To achieve this result, southwest Virginia was transferred from Wheeling to Richmond, and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia was conveyed from Richmond to Wheeling. The Diocese of Wilmington ceded the Eastern Shore of Virginia to the Diocese of Richmond.

The next territorial change of 1974 was the most significant as the Diocese of Arlington was created to encompass northern Virginia. Consequently, the Diocese of Richmond transferred 21 counties and 5 independent cities’ worth of territory – 49 parishes, seven missions and 93 priests – to the new diocese.

Northern Virginia had been geographically and culturally distinct from the rest of the territory of the Richmond Diocese for some time. That area experienced its first growth spurt following U.S. entry into World War I (1917). The construction of the Key Bridge (1923) was decisive since it permitted trolley cars to cross the Potomac River. It was then that northern Virginia became a suburb of Washington, D.C.

Sizeable growth occurred in northern Virginia during and after World War II (1939–1945). In addition to a nationwide population boom, Catholics from other states came to the area to work for the federal government, including the military and related industries, all of which continued to expand during the postwar era.

The number of Catholics in the Diocese of Richmond nearly quadrupled, from 38,000 to 145,000, during the tenure of Peter L. Ireton (1935–1958), the ninth bishop of Richmond. The growth of the Catholic population, based mostly in northern Virginia, accelerated during the time of Ireton’s successor, Bishop John J. Russell (1958–1974).

The new Diocese of Arlington and the reconfigured Diocese of Richmond were disparate neighbors. Whereas Arlington was geographically small (6,500 square miles), mostly suburban, densely populated and wealthier, Richmond was geographically extensive (33,000 square miles), largely rural, sparsely populated and poorer. With this territorial change, Richmond resumed its historical identity as a missionary diocese.

Furthermore, the two dioceses were ideologically divided concerning the legacy of Vatican Council II (1962–1965), as more traditional priests generally went to the Diocese of Arlington and more progressive priests chose the Diocese of Richmond.

The founding of the Arlington Diocese and the territorial reconfiguration of the Richmond Diocese took place following the retirement of Bishop Russell (1973). Walter F. Sullivan, an auxiliary bishop of Richmond (1970), administered the diocese for over a year (1973–1974).

On June 13, 1974, the batch of changes was announced, including the appointment of Sullivan as the 11th bishop of Richmond. Bishop Sullivan was installed on July 19, 1974. He administered northern Virginia (along with eastern panhandle of West Virginia), until the other territorial changes took effect on August 13, 1974, when Thomas J. Welsh was installed as the first bishop of Arlington.

A decree issued by Archbishop Jean Jadot, the papal representative to the bishops to the United States, dated August 2, 1974, explained the forthcoming establishment of the Diocese of Arlington:

By the Apostolic Letter Supernae Christifidelium, dated the 28th day of May, 1974, our Holy Father, Paul VI, graciously committed to us the duty of making effective everything contained therein. Therefore, through the faculty granted to us, we hereby decree and command the following:

1. A new Diocese is established from territory separated from the Diocese of Richmond; the new Diocese will take its name from the County of Arlington;

2. The new Diocese will be a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Baltimore;

3. All documents pertaining to the new Diocese are to be transferred to its archives as soon as possible;

4. There is to be a fair and equitable distribution of diocesan assets.

5. Priests will belong to the new Diocese as indicated in the Apostolic Letter; seminarians, who were either born within its territory or have a legitimate domicile there, will also belong to the new Diocese; other seminarians are to be equitably assigned to one or the other Diocese with the prior approval of all concerned;

Finally, we wish and direct that this our Executorial Decree become fully effective and have juridic force on the 13th day of August, 1974.

In proof whereof, we have signed this decree with our own hand and have ordered that the Seal of the Apostolic Delegation be affixed hereto.

Given at Washington, from the Apostolic Delegation, on this 2nd day of August, 1974.

Jean Jadot

Apostolic Delegate.

A LOST APOSTOLIC BRIEF: THE FOUNDING DOCUMENT OF THE DIOCESE OF RICHMOND

The July 27 issue of The Catholic Virginian featured a translation of the apostolic brief for the establishment of the Diocese of Richmond. The following article, written by Father Anthony E. Marques, chair of the Diocese of Richmond’s Bicentennial Task Force, explains the brief and provides insight into life during the early decades of the diocese.

“On the 12th inst. [August] I received the Apostolic letters dismembering the Archdiocese of Baltimore, erecting the State of Virginia into the church of Richmond and constituting me as its Bishop. …I am at present pennyless and cannot reckon upon any thing as my own to meet the expenses of my voyage except what may result from the sale of my horse and furniture. …

“I have received no additional information concerning the state of things in Norfolk beyond what you [Father John Rice, an influential priest in Vatican affairs] mentioned in your letter and what his Eminence the Cardinal Prefect [Francesco Fontana, head of the Vatican department in charge of overseas missions: Propaganda Fidei] communicated in a letter which accompanied my apostolic letters. This circumstance creates me much uneasiness and will, I am certain, keep me restless until I shall have set out on my journey” (August 31, 1820).

Patrick Kelly (1779–1829), a priest of the Diocese of Ossory in Kilkenny, Ireland, had just been ordained a bishop. He was preparing to cross the Atlantic Ocean to take up his position as the first bishop of Richmond (1820–1822).

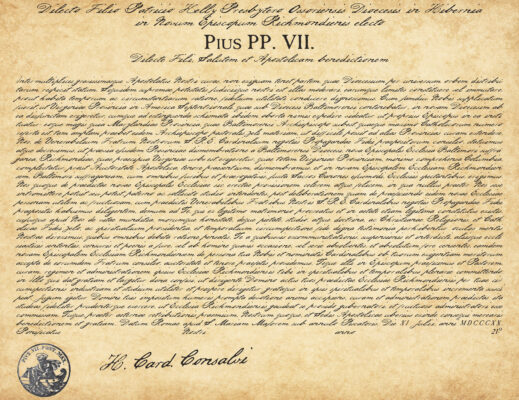

Pope Pius VII (reigned 1800–1823) had established the Diocese of Richmond on July 11, 1820. Kelly was the president of St. John’s College, a seminary in Birchfield, Ireland, at the time of his appointment to Richmond.

In the above letter, Bishop Kelly used the terms “apostolic letters” and “bull” interchangeably to refer to the document that founded the Richmond Diocese and named him as its bishop. It was technically an apostolic brief, and Kelly probably received several copies of it.

Beginning in the late 18th century, for a period of time the brief replaced the bull as the standard document issued by the Vatican to announce and certify the appointment of bishops. This was likely because bulls were expensive to produce and mail.

Both the bull and brief were written on vellum (calfskin parchment) but carried different forms of authentication. The “bull” took its name from the lead seal (Latin: bulla, meaning “bubble,” referring to the appearance of the seal), which functioned as the pope’s signature.

By contrast, the “brief” (Latin: breve, meaning “short”) was a less formal decree that used a wax seal, and later an ink stamp, of the papal fisherman’s ring for authentication.

The brief Kelly received explained why the Richmond Diocese had been established: “Since it seems to be very expedient for the extinction of the schisms which have arisen in it… We…have established and decreed that… a new… Church… be erected at Richmond… and that it should embrace the whole State of Virginia.”

In additional correspondence, the Vatican instructed Kelly to begin his ministry in Norfolk. There he should try to overcome the schism, meaning the formal division among believers, which was mentioned in the brief, and then proceed to Richmond.

The Norfolk Schism (ca. 1794–1821) had arisen over the question of authority: Who could own Church property and appoint pastors — the archbishop of Baltimore, who had responsibility for Virginia at that time, or the lay leaders (trustees) of the Catholic community in Norfolk? Officials at Propaganda Fidei eventually decided that the way to resolve the Norfolk Schism was to appoint a local bishop who would assign priests for the territory of the new diocese.

Patrick Kelly was chosen in part because his Irish nationality could appease the trustees. They had requested an Irish bishop on the pretext that such a prelate could effectively minister to the Norfolk Catholic community, which was largely composed of Irish and French immigrants.

When he arrived in the United States, Bishop Kelly disembarked in New York. He then traveled to Baltimore, where he presented his credential (brief) to Archbishop Ambrose Maréchal (1764– 1828). The archbishop had strenuously opposed the creation of a diocese in Virginia and was openly hostile to Kelly.

From Baltimore, the first bishop of Richmond traveled by ship to Norfolk, arriving on Jan. 19, 1821. Kelly soon celebrated Mass at a chapel there named St. Patrick’s, where he presented his apostolic brief to the local community.

The Norfolk Schism, which had brought Kelly to Virginia, eventually subsided as belligerents left the area. Bishop Kelly remained in Norfolk, but with no income from the local community, he opened a school to support himself.

Less than a year after Kelly’s arrival, the Vatican realized that the Diocese of Richmond had been established prematurely. Kelly was appointed bishop of Waterford and Lismore in Ireland, and the archbishops of Baltimore administered the Diocese of Richmond for the next 19 years (1822–1841). Bishop Kelly left Norfolk in June or July 1822, having never reached Richmond.

What became of the original apostolic brief establishing the Diocese of Richmond is a mystery. Like the diocese itself in the period after the Norfolk Schism, the founding document faded from view.

There are, however, copies of the brief in three archives, with minor variations among them: the Archdiocese of Baltimore, Propaganda Fidei (today the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples), and the Vatican Apostolic Archives (formerly the Vatican Secret Archives).

An artistic reproduction of the founding document and a translation were commissioned for the bicentennial of the Diocese of Richmond. This facsimile and translation are included in the bicentennial commemorative book, “Shine Like Stars” (Éditions du Signe, 2019).

The disappearance of the actual document that established the Diocese of Richmond mirrors the loss, for two decades, of a residential bishop of this local Church. The text of the decree, which has survived, is therefore a precious link to the past.

This “relic” can help Catholics in the diocese today to appreciate the hardships of that time, as well as the fortitude and perseverance that have brought the Richmond Diocese to its bicentennial jubilee.

Editor’s note: The bicentennial commemorative book, “Shine Like Stars,” is available for purchase at parishes in the Diocese of Richmond.