The Catholic Church believes that every person is created in the “image of God.” We are made in the image of a community of persons – Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Our God-given human rights develop and thrive in community.

Our human dignity is both personal and social. We need one another to grow, to prosper and to reach our full potential.

This basic teaching is not alien to Americans. Our Declaration of Independence pronounces: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The declaration goes on to acknowledge that “to secure these rights, Governments are instituted.”

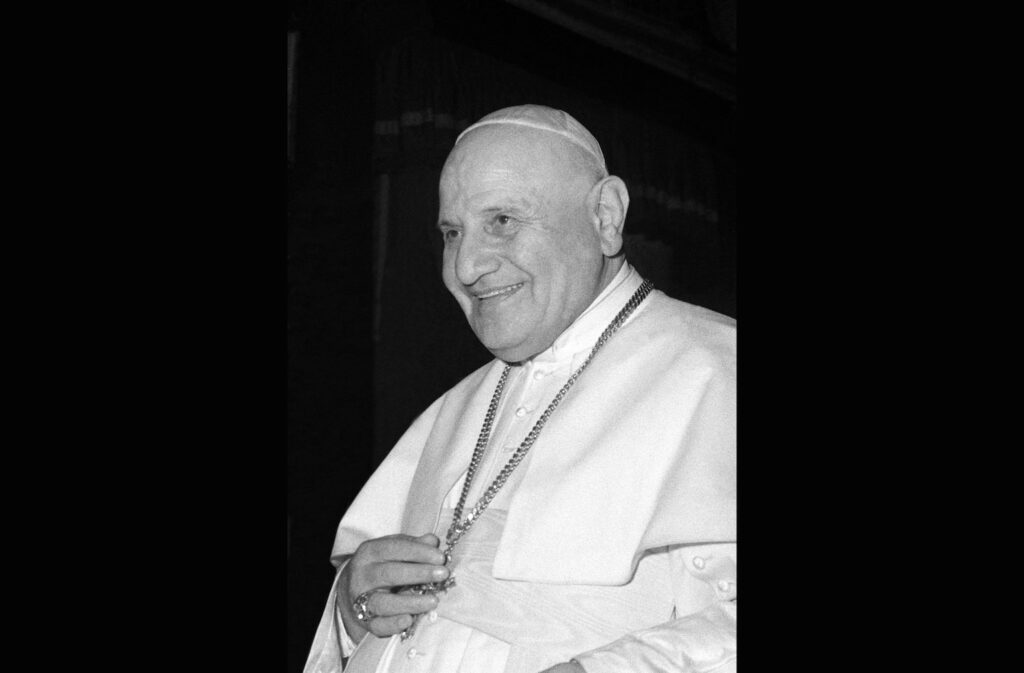

Our nation is not alone in uplifting human rights. St. John XXIII said, in the encyclical “Pacem in Terris,” the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948, was “a solemn recognition of the personal dignity of every human being” (No. 144).

Sadly, our nation and others have not always lived up to our commitments to human rights. Sometimes we have not even properly understood these rights.

Discrimination based on race, ethnicity, religion, sex and other factors is evidence of our shortcomings; the failure to consistently defend the right to life is another.

It is true that “I have rights.” It is also incomplete. It would be better to say, “We all have rights.” Even this is incomplete. In the words of Pope John XXIII, human rights “are inextricably bound up with as many duties” (No. 28).

Only by exercising both our human rights and responsibilities can we protect the rights of all.

When Americans think of rights, we often focus on freedom of religion, assembly, speech and the press as found in the Bill of Rights. Catholic teaching includes these rights and many more.

For the Church, human rights extend to the social structures that are needed for a life worthy of human dignity. These structures serve the common good.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that the common good is necessary for promoting human rights. Quoting the Second Vatican Council, the Catechism defines the common good as “the sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily” (No. 1906).

“In the name of the common good, public authorities are bound to respect the fundamental and inalienable rights of the human person” (No. 1907).

Governments “should make accessible to each what is needed to lead a truly human life: food, clothing, health, work, education and culture, suitable information, the right to establish a family, and so on” (No. 1908).

Pope John XXIII explored many of these rights in “Pacem in Terris.” He began with “the right to live” and went on to affirm the “the right to bodily integrity and to the means necessary for the proper development of life, particularly food, clothing, shelter, medical care, rest, and, finally, the necessary social services.”

He acknowledged the “right to be looked after in the event of ill health; disability stemming from his work; widowhood; old age; enforced unemployment; or whenever through no fault of his own he is deprived of the means of livelihood” (No. 11).

This holistic understanding of “inalienable rights” and the common good makes moral demands upon us. Beyond respecting ourselves and the rights of others, it “is necessary that all participate, each according to his position and role, in promoting the common good,” states the Catechism. (No. 1913).

In other words, we have both personal and social responsibilities that correspond to our rights. The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church puts it this way: “The common good therefore involves all members of society, no one is exempt from cooperating, according to each one’s possibilities, in attaining it and developing it” (No. 167).

Government serves “the common good when it seeks to create a human environment that offers citizens the possibility of truly exercising their human rights and of fulfilling completely their corresponding duties” (No. 389). Especially in a democracy, we have both rights and duties.

St. John Paul II reminded us in “Sollicitudo Rei Socialis” that “the goods of this world are originally meant for all.” He reaffirmed the “right to private property,” but taught that it is not absolute and was “under a ‘social mortgage’” (No. 42).

In “Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship,” Pope Francis warned that “in practice, human rights are not equal for all” (No. 22). “Today there is a tendency to claim ever broader individual – I am tempted to say individualistic – rights” (No. 111).

There is a danger in detaching individualistic rights from the common good. Such detachment leads to excessive inequality. “Development must not aim at the amassing of wealth by a few, but must ensure ‘human rights – personal and social, economic and political, including the rights of nations and of peoples,’” he wrote (No. 122).

As Catholics and human beings, our vocations are to exercise our own rights to develop our human potentials and to build a society in which others can do the same. Protecting human rights is linked to promoting the common good.

Stephen M. Colecchi retired as director of the Office of International Justice and Peace of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2018. He currently serves as an independent consultant on Catholic Social Teaching and international issues of concern to the Church.