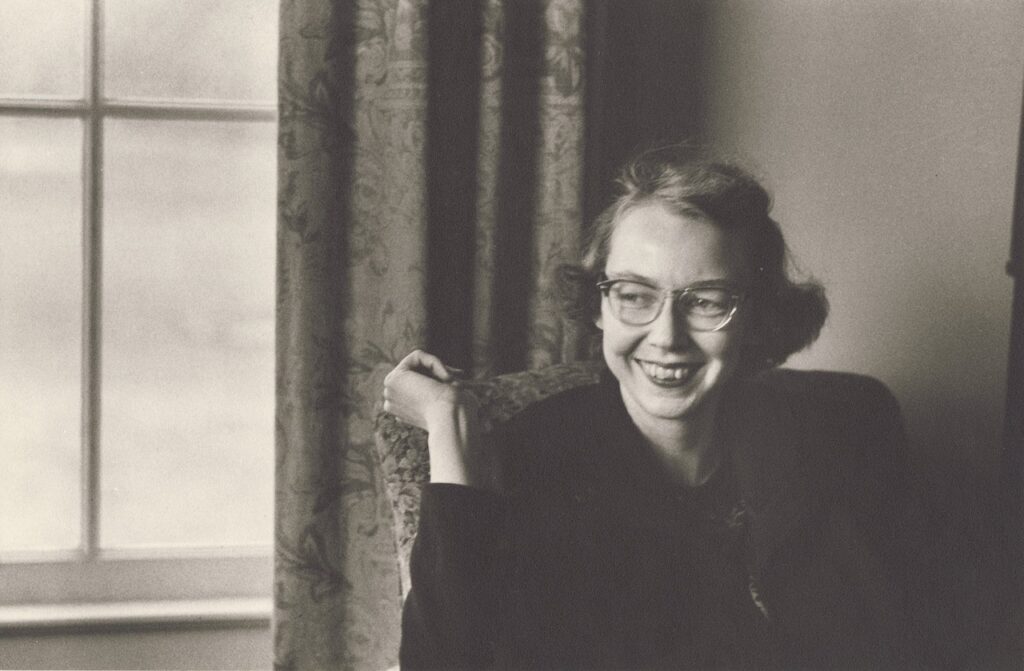

(OSV News) — Flannery O’Connor was not an evangelist. She was an artist, one of the most gifted American fiction writers of the 20th century. But a profoundly Catholic theological vision informs her art, giving her stories resonance and depth that sound deep — and sometimes deeply disturbing — spiritual chords.

Explaining why she often wrote about grotesque characters in bizarre situations, O’Connor remarked that in an age of disbelief like this one, “You have to make your vision apparent by shock — to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.”

Another time she said, “All my stories are about the action of grace on a character who is not very willing to support it.” Then, with her characteristic mixture of ruefulness and realism, she added, “But most people think of these stories as hard, hopeless, brutal, etc.”

Today, 60 years after her death, that sort of reaction to O’Connor’s fiction is more and more giving way to the realization that these are richly imagined analogies of faith flung in the face of skeptical secularism by a master storyteller.

Writing in the New York Review of Books, author Joyce Carol Oates cited O’Connor’s “unshakable absolutist faith” as the foundation of her creative work. Faith, said Oates, provided O’Connor with “a rationale with which to mock both her secular and bigoted Christian contemporaries in a succession of brilliantly orchestrated short stories that read like parables of human folly confronted by mortality.”

The only child of a real estate agent named Edward F. O’Connor and Regina Cline O’Connor, Mary Flannery O’Connor was born March 25, 1925, in Savannah, Georgia. Her great-grandparents were Irish immigrants, and the family had remained staunchly Catholic, members of a religious minority in the Protestant Bible Belt. As a child, Mary Flannery attended parochial schools until her father’s failing health forced a move to the Cline family home in Milledgeville, Georgia. There she attended Peabody High School, drawing cartoons and writing for the school paper.

In 1942, she entered Georgia State College for Women, located near her home. It was then she began to use the name Flannery O’Connor on school assignments. She graduated with a degree in social science.

In 1946, she was accepted by the prestigious Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa and went there to study journalism. While there, she met important writers like Robert Penn Warren and John Crowe Ransom, began writing fiction and started attending daily Mass. After Iowa, she spent time at an artists’ colony near Saratoga, New York, writing and socializing with other writers and attending Mass with the domestic staff.

Taken ill in 1950 while traveling home for Christmas, she was diagnosed with lupus, the inflammatory connective tissue disease that had also killed her father. She moved home for good and lived with her mother, settling into a routine of writing, tending her collection of peacocks and other exotic birds, exchanging letters with a growing number of correspondents, going to church with her mother, now and then lecturing on college campuses, and battling lupus.

Her illness she viewed with cool courage touched by humor. “I had a blood transfusion Tuesday,” she wrote a friend not long before her death, “so I am feeling sommut better and for the last two days I have worked one hour each day and my my I do like to work. I et up that one hour like it was filet mignon.”

Her first novel, “Wise Blood,” appeared in 1952 and received respectful but sometimes puzzled reviews. The story, she later told one of her correspondents, is about a “Protestant saint,” Hazel Motes by name, “written from the point of view of a Catholic.” Her second novel, “The Violent Bear It Away,” about a reluctant teenage prophet named Tarwater, came out in 1960.

In between, she produced a slow but steady stream of short fiction. The stories were collected in two volumes, “A Good Man Is Hard To Find” (1952) and the posthumously published “Everything That Rises Must Converge” (1965).

The unraveling of hypocrisy is a favorite theme with O’Connor, and a story called “Revelation” is a particularly striking example of that. Mrs. Turpin, a middle-aged farm woman possessing sublime self-satisfaction and a keen eye for the faults of those she considers her inferiors, gets the shock of her life when a crazed girl in a doctor’s office throws a book at her, tries to choke her and tells her, “Go back to hell where you came from, you old wart hog.”

It’s the start of Mrs. Turpin’s conversion. That evening, as she stands beside her hog pen, the conversion comes to completion in the vision of a “vast horde of souls” mounting to heaven.

Leading the way are many of those she’s always looked down on. Bringing up the rear are some like herself. “They were marching behind the others with great dignity, accountable as they had always been for good order and common sense and respectable behavior. … Yet she could see by their shocked and altered faces that even their virtues were being burned away.”

Mrs. Turpin walks slowly back to the house. The crickets are loud in the woods, “but what she heard were the voices of the souls climbing upward into the starry field and shouting hallelujah.”

Beyond mere hypocrisy, O’Connor sometimes confronts monstrous evil that might best be described as demonic. In “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” an escaped killer called the Misfit slaughters a family whose grandmother confronts him at the end.

“No pleasure but meanness,” he snarls at her.

“She saw the man’s face twisted close to her own as if he were going to cry and she murmured, ‘Why you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children.’ She reached out and touched him on the shoulder. The Misfit sprang back as if a snake had bitten him and shot her three times through the chest.”

“She would of been a good woman,” he tells his companions, “if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

O’Connor rejected the stereotyped explanation that she wrote as she did because that was how writers of the so-called Southern Gothic school wrote.

“My own feeling is that writers who see by the light of their Christian faith will have, in these times, the sharpest eyes for the grotesque, for the perverse, and for the unacceptable. … The novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural; and he may well be forced to take ever more violent means to get this vision across to this hostile audience.”

In 1960, the Dominican Servants of Relief for Incurable Cancer, a religious order founded by Nathaniel Hawthorne’s daughter, Rose, that operated a cancer home in Atlanta, approached O’Connor with a request to write a book about a girl with a disfiguring facial tumor whom the sisters had sheltered until her death at the age of 12. The sisters were deeply impressed by her courage and good spirits and wanted the world to know about her.

O’Connor told them they should write the book themselves, but she negotiated its publication and wrote the introduction.

The volume appeared in 1961 as “A Memoir of Mary Anne.” Reflecting its author’s own experience, her introduction is an extraordinary testimony of faith.

“One of the tendencies of our age is to use the suffering of children to discredit the goodness of God,” she wrote, “and once you have discredited his goodness, you are done with him.” In earlier times, people viewed unmerited suffering with “the blind, prophetical, unsentimental eye of acceptance, which is to say, of faith.” But now “we govern by tenderness” — tenderness divorced from its source in Christ — which “ends in forced labor camps and in the fumes of the gas chamber.”

O’Connor died of kidney failure brought on by lupus shortly after midnight Aug. 3, 1964. Her volume “The Complete Stories” received the National Book Award for Fiction in 1972.