By definition, trauma is a painful experience that disturbs and distresses the one who experiences it; it causes us to believe that we are fundamentally unsafe and constantly at risk, even in environments that may have felt safe before. Trauma is also isolating; it can often convince us that we are not only alone in our suffering, but also that there is no one who could possibly help or heal us.

Trauma is part of what the two disciples on the road to Emmaus (Lk 24:13-17) were reckoning with when they encountered, unbeknownst to them, the risen Lord Jesus. Anxious, depressed and shocked, the disciples were discussing with one another the death of their close friend and master.

As they walked and talked, they might have felt terrified, experienced viscerally the grief in their bodies, and perhaps struggled accepting a “new normal.” When the disguised Jesus encountered them, he inquired, “What are you discussing as you walk along?”

The disciples spoke of the events of his passion, and uttered one of the most painful, authentically human verses in all of Scripture: “But we were hoping that he would be the one to redeem Israel; and besides all this, it is now the third day since this took place” (Lk 24:21).

With this answer, the two disciples voice the trauma of being separated from life as they knew it before.

Although it may seem strange to describe it as such, the pandemic we are currently living through can also be described as a collective trauma. The events of the past few months have upended many of our lives, caused many of us great distress, separated us from our loved ones, and left all of us pondering the meaning of it for the rest of our lives.

Just like the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, we may have found ourselves tearful and shocked at many points in the past few months for a variety of reasons, saying, “But we were hoping …”

If at the root of any traumatic experience is isolation, insecurity and exclusion, then healing is cultivated through safety, security and inclusion. In other words, one of the ways in which trauma can be healed is through relationship.

Relationships cultivate the healing of those who have experienced trauma because they provide a space of safety and security in which we are known by another.

On the road to Emmaus, Jesus gives us this example of healing through relationship and accompaniment. Instead of admonishing the two disciples for experiencing the real effects of a trauma by coldly instructing them on the theological purpose of his passion and death, he invites them into relationship by meeting them where they are.

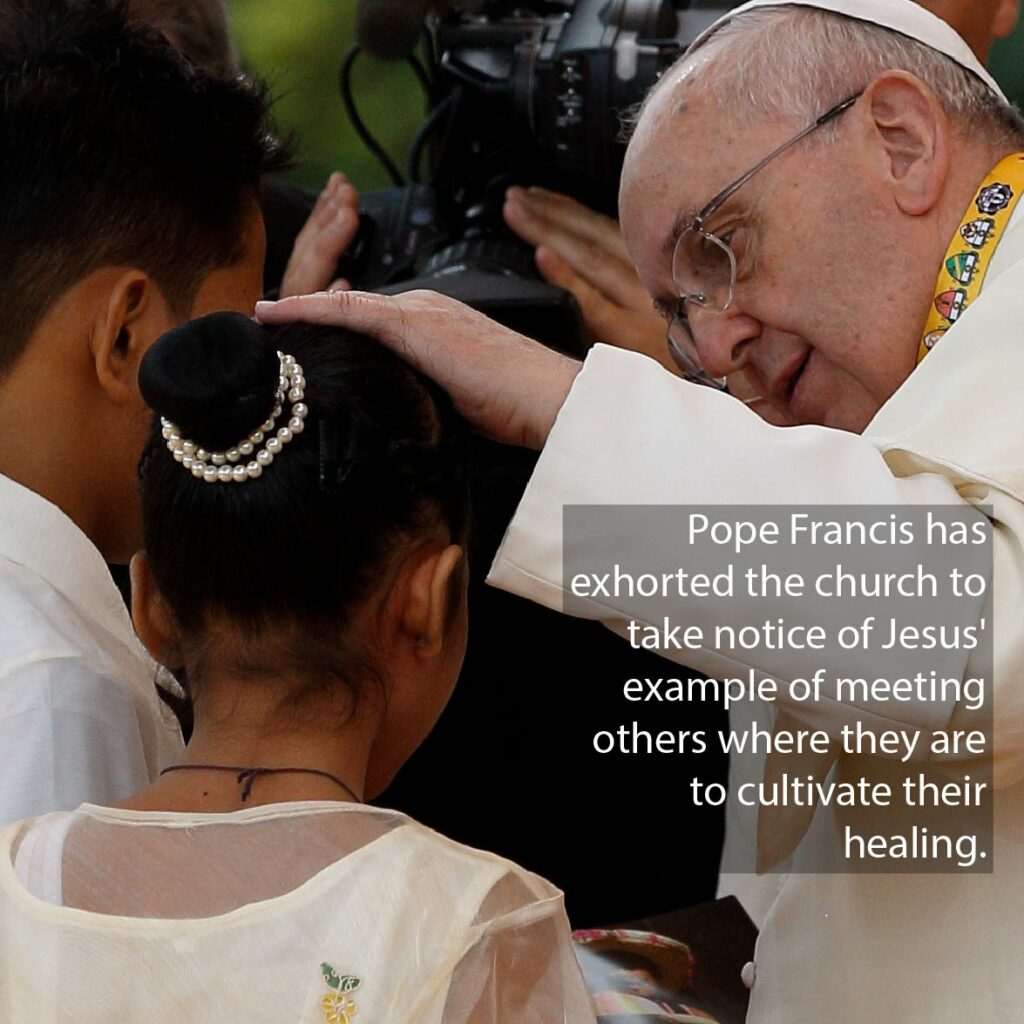

Pope Francis has exhorted the church to take notice of Jesus’ example of meeting others where they are to cultivate their healing. In “Evangelii Gaudium” (“The Joy of the Gospel”), he spoke of the need for the church to be initiated into the “art of accompaniment” (No. 169).

An approach to pastoral ministry that involves an intentional relationship formed by a more seasoned mentor in faith and the one they accompany in safety and trust, accompaniment helps us seek and respond to God more readily in our everyday lives.

Imitating Jesus’ example on the road to Emmaus, the point of departure for accompaniment is the real-life experience of the one who is accompanied, from which a mentor creates a space of relationship and acceptance. By its nature, accompaniment is the opposite of trauma and separation: It “heals, liberates and encourages growth in the Christian life,” says Pope Francis (No. 169).

Through accompaniment, another person helps guide us in our pursuit of holiness by assisting us in recognizing where in the messiness, chaos and defeat in our lives the Spirit is, has been and is still inviting us to go.

What does accompaniment ask of us in this time of collective trauma?

It asks us not to remain idle, wishing that circumstances were different. It requires us to imitate Jesus and take the first step toward those on the journey who, like the disciples, are suffering from the trauma of the past few months.

Jesus doesn’t wait for the ideal situation to encounter the disciples; he meets them on the way. We are called to go in the same haste with which Jesus accompanied his disciples, whether that is on Zoom, a phone call or social media.

It calls us to recognize that we can offer virtual accompaniment through offering encouragement to a loved one in a Zoom call, checking in on our friends via direct messages on social media or calling our family from miles away.

As Jesus created a space of healing for the disciples by accepting their frame of reference, so too are we called to accompany those in our care in our current frame of reference: through screens and technology.

In his Letter to the Romans, St. Paul asks, “What will separate us from the love of Christ?” (8:35) Through accompaniment, we can answer that nothing, not even the collective trauma of a pandemic, can separate us from Christ, and therefore, one another.

Campbell is coordinator of formation programs at the Catholic Apostolate Center, co-author of “The Art of Accompaniment: Theological, Spiritual and Practical Elements of Building a More Relational Church,” and a doctoral candidate in catechetics at The Catholic University of America.