In the spartan confines of her Polish convent, St. Faustina had a wonderful vision on the night of Feb. 22, 1931.

Jesus appeared to her, clothed in white, his tunic cinctured. “One hand [was] raised in the gesture of blessing, the other was touching the garment at his breast,” St. Faustina wrote in her diary. “From beneath the garment, slightly drawn aside at the breast, there were emanating two large rays, one red, the other pale.”

Jesus then commanded her to have an image of the vision made. She recorded his words in her diary: “Paint an image according to the pattern you see, with the signature, ‘Jesus, I trust in you.’ I desire that this image be venerated, first in your chapel, and then throughout the world. I promise that the soul that will venerate this image will not perish.”

The same night, St. Faustina recorded the Lord’s request that the second Sunday of Easter become the Feast of Mercy: “I desire that the Feast of Mercy be a refuge and shelter for all souls, and especially for poor sinners. … The soul that will go to Confession and receive Holy Communion shall obtain complete forgiveness of sins and punishment” (Diary, 699).

At St. Faustina’s canonization in 2000, Pope St. John Paul II named the second Sunday of Easter the Sunday of Divine Mercy. The Holy Father approved a decree which grants a plenary or partial indulgence to the faithful who observe Divine Mercy Sunday. A plenary indulgence removes all of the temporal punishment that a person deserves for his sins.

“We know that Jesus keeps his promises,” said Daniel diSilva, founder of the Original Divine Mercy Institute. One of the world’s leading experts on the Divine Mercy devotion, diSilva spoke at Mary Mother of the Church Abbey, Richmond, on March 19.

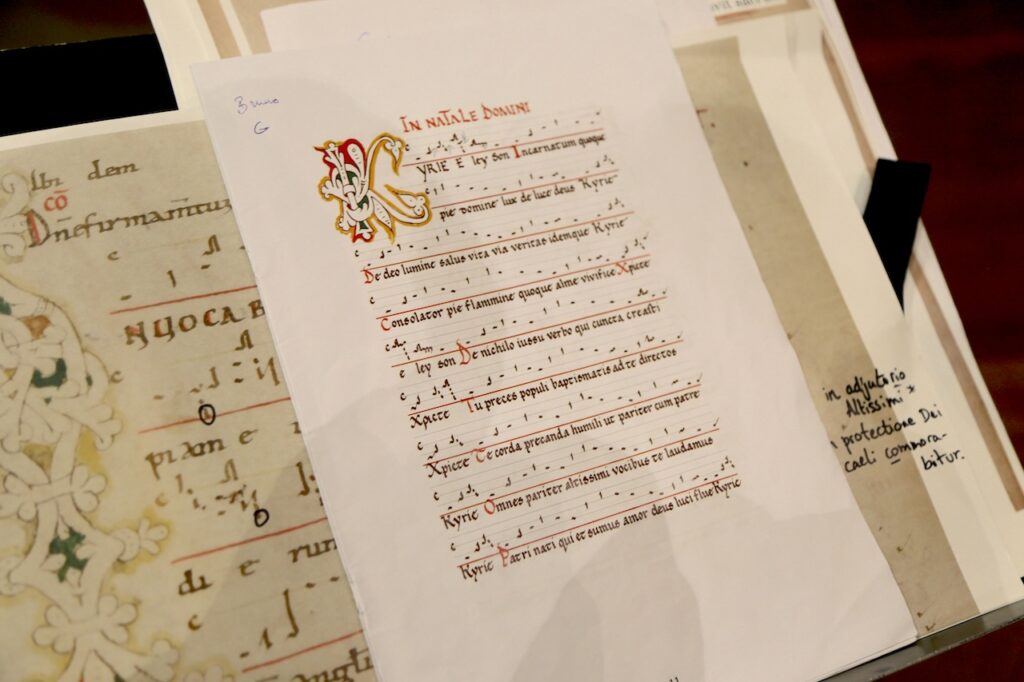

He gave a presentation on the Divine Mercy image and its spiritual blessings before the Divine Mercy Choir performed at the abbey. Originally from Lithuania, the choir is currently in the middle of a monthlong tour of the U.S., performing sacred music that would have been known to St. Faustina. The previous night, they had performed at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City.

The famous Divine Mercy image was painted according to St. Faustina’s instructions in 1934 by Eugeniusz Kazimirowski in Vilnius, Lithuania. Another version, well-known in the United States, was completed by Adolf Hyla in 1943. As Jesus asked, the image came to be venerated across the world.

When St. Faustina first saw the image, she burst into tears, lamenting that no artist could ever capture the glory and beauty she had witnessed. However, diSilva emphasized that this does not mean St. Faustina disliked the image, which she promoted until her death in 1938. He compared her reaction to an episode in the life of St. Thomas Aquinas.

“St. Thomas Aquinas wrote ‘Summa Theologica,’ a foundational text of Catholic philosophy,” said diSilva. “Towards the end of his life, he had a vision of heaven, and afterwards, he said of ‘Summa Theologica,’ ‘Burn it – it is all straw.’ The glory of God is beyond anything man can recreate.”

Ancient musical tradition

While no artist could recreate the glory of God, the Divine Mercy Choir was able to closely replicate the music St. Faustina would have heard as an Eastern European nun in the 1930s.

For over an hour, Gabija Vaičiulienė, Tautvydas Mazeika, Antanas Pundzius and Bruno Champagne performed traditional Latin chants and Eastern European melodies, transporting the audience to a timeless place. Vaičiulienė, who studies Gregorian chant at the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome, is the group’s director and founder.

Though the melodies they perform date back in some cases to the late Roman Empire, the choir retains the privilege to harmonize and improvise.

“Originally, [Old Roman] chant is written in monophony [written for one voice],” said Vaičiulienė. “But if you look at other chant traditions, like Byzantine chant, or any singing tradition, you find polyphony [multiple voices]. So that is why we dare to add it.”

For example, the group performed “Offertorium Terra Tremuit,” an Old Roman chant first written down in the 11th century with an oral tradition dating back to the days of the Caesars. The chant is written for one voice, but while Vaičiulienė sang the main melody, the others sang deep, powerful notes that fused together in a thundering meditation on God’s majesty.

“In this setting of traditional music, there is not exactly [a distinction between] the composer and the person who sings it,” explained Champagne. “They are always intertwined. Every time we perform, we might change something.”

The basics, though, have been prescribed for more than 1000 years. In an Eastern European world where Orthodox and Catholic traditions grew side-by-side, the songs were ones that St. Faustina would have known. The group also performed Lithuanian and Polish hymns.

St. Faustina’s story – from her life as a Polish nun to her ecstatic visions and the painting of the Divine Mercy image – was told at intervals throughout the performance. On the altar were relics of St. Faustina – a piece of bone – and of Blessed Michael Sopocko, her confessor.

One of the most important parts of the Divine Mercy devotion is the Divine Mercy Chaplet, given by Jesus to St. Faustina. The devotion is prayed using rosary beads, but with different prayers. On each Hail Mary bead, the faithful recite, “For the sake of his sorrowful passion, have mercy on us and on the whole world.” The program opened with the recitation of the Divine Mercy Chaplet.

In the back of the abbey, Hyla’s second Divine Mercy image is prominently placed, along with the words, “Jezu ufam Tobie,” Polish for “Jesus, I trust in you.”

“Both images are very nice,” said Ludmila Kovar, who attends Mass at the abbey and was at the performance. She enjoyed listening to diSilva’s presentation on the original image by Kazimirowski. But of Hyla’s version, she said, “When Christ looks at you that way, it hits you, too.”

Kovar grew up in Czechoslovakia, where she said St. Faustina is well-known. “When I was a child, I didn’t know all the history and the impact that St. Faustina had, but I definitely knew the picture,” she said.

In his presentation, diSilva pointed out key details – the purple halo, for instance, is a sign of royalty, while the red and white beams intermingle, like the water and blood that flowed from Jesus’ side.

“We look at this image, and we let it take us wherever Jesus wants it to take us,” he said.