(OSV News) – Their births were separated by almost a century, but Venerable Father Augustus Tolton (1854-1897) and Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman (1937-1990) both endured and triumphed against the sin of racism in their own eras and in the Catholic Church, offering future generations of every race a timeless legacy of what it means to live in the freedom of following Jesus Christ.

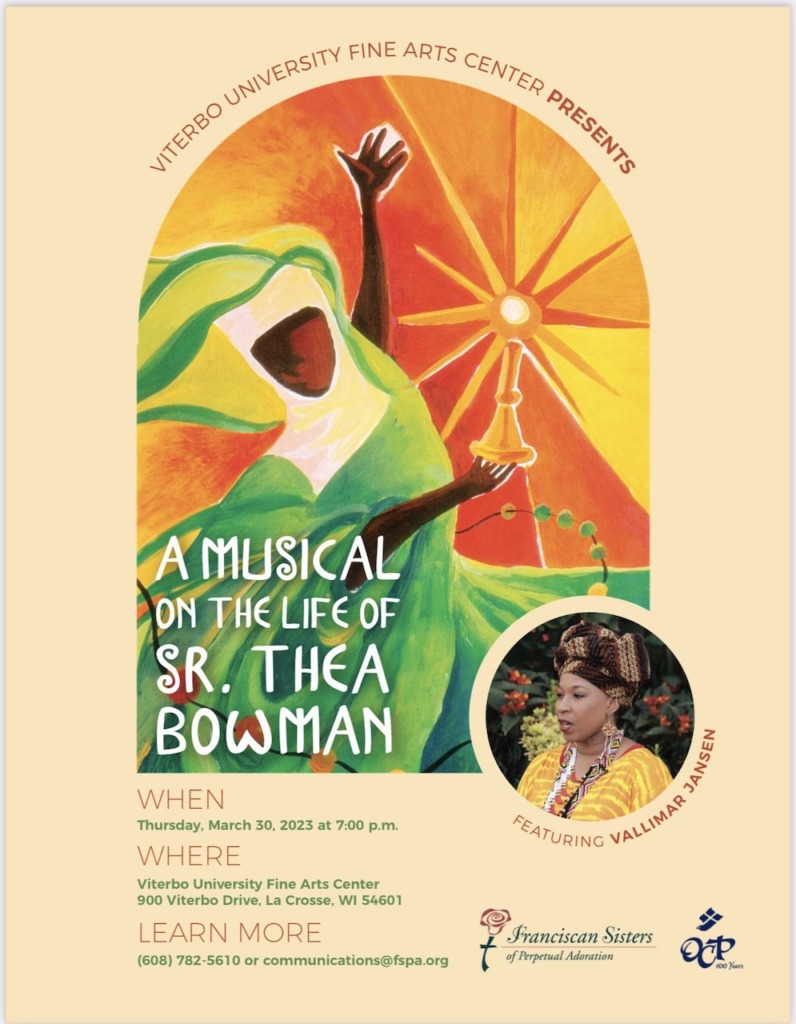

As they progress toward sainthood, and the possibility of becoming the first recognized Black Catholic saints of the United States, Father Tolton’s and Sister Thea’s lives are inspiring theater audiences from coast to coast in two plays, St. Luke Productions’ “Tolton: From Slave to Priest” and ValLimar Jansen’s “I Will Live Until I Die.”

“I was in Springfield Diocese in Illinois,” shared touring actor Leonardo Defilippis, “and this country priest – a pastor – gave me a book on (Tolton), a prayer card and a picture of him.”

Defilippis is founder and president of St. Luke Productions, a theatrical company that brought Father Tolton’s story to the stage, as well as those of many other saints. The priest asked, “Leonardo, why don’t you do a show on him?”

Returning home with the question lingering, Defilippis put the picture in his office. The steady gaze of Father Tolton peered from the bookshelf where it was placed. “I kept looking at him. His eyes – if you’ve ever seen a picture of him – they’re very piercing,” Defilippis told OSV News. “So I decided, I’m going to take a risk and do it.”

Born to enslaved parents in Missouri, Augustus Tolton, two siblings and his mother, Martha Tolton, fled to Illinois for freedom in 1862 after his father, Peter Tolton, escaped to join the Union Army during the Civil War.

An Irish priest, Father Peter McGirr, encouraged young “Gus,” as he was known, to consider the priesthood. No U.S. Catholic seminary would then admit African Americans, so in the face of this racist opposition, Augustus Tolton eventually studied for priesthood in Rome. He was ordained in 1886 – the first publicly known African American Catholic priest – and instead of becoming a missionary to Africa, as he expected, Father Tolton returned to the U.S., serving in two Illinois cities, Quincy and Chicago, before dying of heat stroke in 1897.

“Tolton: From Slave to Priest,” which uses multimedia projections and music, has been seen by 65,000 Catholics in parishes, seminaries and schools. Audiences newly aware of Father Tolton have responded by asking his intercession and praying to him, which may assist his sainthood cause.

“His story is one of unity,” Defilippis said, “one of peace and forgiveness, and the complete trust in God – that God will take care of us.”

In the role of Father Tolton is veteran television and stage actor Jim Coleman. “It is my mission to share his story,” Coleman told OSV News. “It is something that has become my passion.”

The production also is impacting vocations. Coleman shared that seminarians have told him, “’This is the push I needed. I was close to giving up – and then to see what he had to go through makes me realize I have nothing to compare to that. My journey is easy.’”

Father Jim Lowe, a Companions of the Cross priest who serves at St. Scholastica Catholic Church in Detroit, recalled the play’s scene of Father Tolton’s first Mass when the play came to his parish March 25. “It was very moving. It felt like I was actually present at his first Mass,” he told OSV News.

Father Lowe detected a presence in that moment – and has no doubt who it was. “In a sense, being at this play brought Father Tolton to life both theatrically and spiritually,” he said. “There is no doubt in my mind that he was interceding on our behalf as we witnessed his heroic life journey.”

After repeatedly being told she reminded people of Sister Thea Bowman, ValLimar Jansen – a singer, composer, recording artist, professor, worship leader and workshop presenter – decided “someone” was sending her a message.

Using as source material the biography penned by a nun who knew Sister Thea, Jansen wrote and arranged a musical, “I Will Live Until I Die,” which takes its title from Sister Thea’s reaction to her cancer diagnosis later in life.

“Her main message was everyone should be valued – everybody’s culture,” Jansen told OSV News. “And to learn what that is; to celebrate it; to bring all that we are to the Eucharistic table.”

Born to African American Methodist parents, Sister Thea was raised in the “Jim Crow” South, with its racial segregation and persistent threat of anti-Black violence. While her grandfather was born under slavery, her father, a physician, actually moved his family from New York to Mississippi to provide medical care to Black families who were denied this basic human right.

After attending a Canton, Mississippi, school staffed by the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration (FSPA), Sister Thea became a Catholic at age 9. As a teenager, she joined the FSPA and later taught, evangelized, earned a doctorate and directed intercultural affairs for the Diocese of Jackson, Mississippi. Breast cancer cut her life short – but not before Sister Thea established a prophetic witness to the Black American Catholic experience. Despite various injustices and limitations she encountered, Sister Thea nonetheless steadfastly maintained, “God makes a way out of no way.”

“ValLimar truly embodied Sister Thea,” said FSPA Sister Laura Nettles, professor and executive director of Mission and Social Justice at Viterbo University in La Crosse, Wisconsin, where Jansen’s musical capped the school’s annual Sister Thea Bowman Celebration Week in March.

“It was a resounding success, a full house with multiple standing ovations,” Sister Nettles told OSV News. “People walked away happy, and singing the spirituals that were so important to Thea.”

Sister Nettles reflected, “This work is especially poignant for my congregation and university given that Sister Thea experienced racism in both. We need Sister Thea’s message and guidance now more than ever.”

The positive reaction of Sister Thea’s own religious community has been important to Jansen – energizing her as she tours the musical nationwide, opening eyes and ears to Sister Thea’s essential teaching. “It wasn’t about a color issue,” explained Jansen. “It was about how we are a family of families.”