When Msgr. Walter Barrett told his mother he wanted to be a priest, she worried that he might be sent to another state or country – until he decided to be a diocesan priest and thus, he told her, he would always be within the Diocese of Richmond and therefore never too far away.

“She was reassured,” he said.

That sense of “being present” has shaped his 47 years as a priest for the diocese.

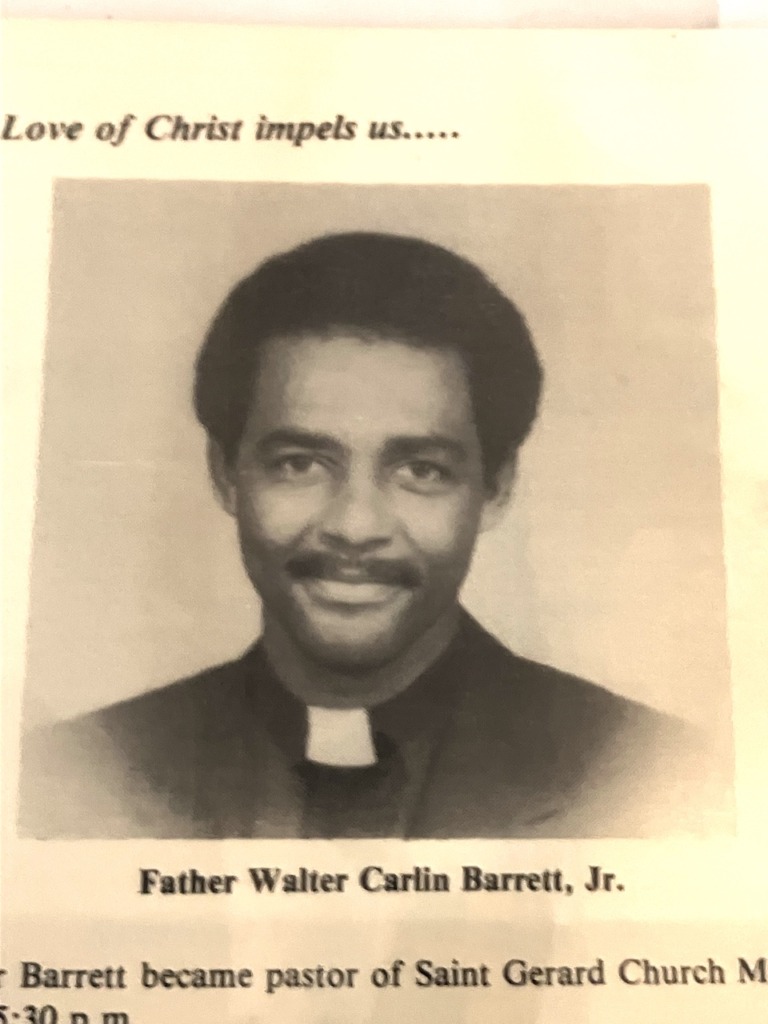

Msgr. Barrett, recently retired at 75, was just the second Black priest in the Diocese of Richmond when he was ordained in 1975, following Father Clarence Watkins. He shared his memories with a gathering of about 60 people at Our Lady of Nazareth (OLN), Roanoke, on Wednesday, Feb. 15, after a potluck dinner.

The event was a joint effort by OLN and Voices of Faith, an organization that fosters connection and understanding among various religious traditions in the Roanoke Valley. Besides local Catholics, the evening included local members of the Mormon and Muslim faiths as well.

Katie Zawacki, Voices of Faith co-founder and OLN parishioner, made the introduction: “With six Black Catholics on their way to sainthood, we thought it would be nice to hear from Msgr. Barrett what it was like to be a Black Catholic, especially here, back in the ’70s and ’80s.”

“I knew Msgr. Barrett when he was at St. Gerard’s,” she said later. “He helped Black Catholics feel seen and acknowledged.”

Life in Roanoke

Msgr. Barrett became the first Black pastor of the mostly Black parish of St. Gerard, Roanoke, from 1977 to 1985. The church had been founded in 1946 by Redemptorist priests to serve Black Catholics in Roanoke, who did not feel welcome at white Catholic churches.

By 1977, Bishop Walter F. Sullivan, urged by Roanoke native and Franciscan Father James Goode (known as the “dean of Black Catholic preachers”), thought it was time for a diocesan priest to lead the small church, and he asked then-Father Barrett to do so. The young priest felt it was important to have pastors who reflected the image of their parishioners, and simply “being present” could help others feel welcome and understood, he explained.

“At [St. Mary’s Seminary and University, Baltimore] seminary I had written my dissertation for my master’s in theology on the need for indigenous clergy in the Black Catholic community,” he said. “Black parishes had been staffed by religious orders, but there’s a different kind of structure and support for diocesan priests.”

He was surprised by the friendliness of Roanoke, he said. “My impression was that people were warm and welcoming; both the Blacks and whites I met were hospitable.”

He recalled attending services that also included local Protestants, Muslims and members of the Greek Orthodox Church, and a Jewish rabbi, all praying for the community together.

“There was a true sense of ecumenism,” he said.

Msgr. Barrett remembered that when he left, he cried with many of his St. Gerard parishioners – some of whom, Black and white, had earlier been uncertain about a Black pastor when he arrived.

“We had come to love each other,” he said.

Longtime St. Gerard parishioners James and Altermease Brown were among those who came to hear their former pastor speak at OLN.

“He was just a very spiritual and understanding priest, friendly to everyone at St. Gerard’s and close to the families,” recalled Altermease Brown.

She added that his mother and her mother, Camille Willis, had become friends when the Barretts visited St. Gerard.

“When my mother died, Msgr. Barrett wrote a beautiful letter that was read at her funeral, and that meant a lot to me,” she said.

Besides his time as pastor in Roanoke, Msgr. Barrett also served at the Basilica of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception, Norfolk; Holy Rosary, Richmond (his home parish); and the Peninsula Cluster (St. Vincent de Paul, Newport News; St. Joseph, Hampton; and St. Mary Star of the Sea, Hampton). He also served as director of the diocesan Office for Black Catholics in 2022.

Journey of faith

Msgr. Barrett later reflected on his early life as a Catholic in Richmond and the path that led him to the priesthood.

He paid tribute to his late mother and father, Elizabeth and Walter Sr., who were not yet Catholics but Baptists at the time, and who supported his Catholic journey anyway.

He also credited his aunt Hattie Barrett Ward, a “very enthusiastic” convert whose life showed him the beauty and strength of her Catholicism when he was a child. She also convinced the Barretts to provide a Catholic education for their three children, Alice, Walter and Douglas.

“It was her example, and the joy of her Catholic faith, that really inspired me,” Msgr. Barrett said. “She encouraged me to grow in my studies and my religious training.”

Msgr. Barrett attended Vande Vyver Catholic School and Cathedral Central High School, and joined Holy Rosary Catholic Church. His Aunt Hattie died in 1974 but saw him ordained a deacon before her passing.

Although he asked to be baptized a Catholic in the third grade, it did not happen until the seventh grade after he’d thoroughly studied the Baltimore Catechism (“I learned it cover to cover”). Part of his studies were with Sister Cecelia Reilly, still living, whom he remembers fondly.

“I think it was often the faith of women that influenced me,” he recalled later. “My aunt, and Sister Cecelia Reilly, and the other nuns who taught me were all so expressive about it.”

When he was finally baptized, despite having considered marry- ing and raising a family someday, he announced that he wanted to become a priest.

“I just knew: I was drawn by the beauty and mystery of the Mass, where I felt the presence of God,” he said. “And after I became a priest I devoted myself to the Black Catholic apostolate.”

Being present, feeling blessed

Speaking by phone from his late parents’ home in Richmond’s East End where he now lives, Msgr. Barrett recalled his widowed moth- er’s last years, when she lived with him in his rectory. At the time he was pastor of the Peninsula Cluster of parishes. Her request to join him required special permission, which was granted first by Bishop Francis X. DiLorenzo and, after his death, continued by Bishop Barry C. Knestout.

It was a blessing to provide a home and, later, caregiving for his mother, he said. When her health began to decline, all three of her children tended to her health needs. Msgr. Barrett was also her spiritual caregiver in her final days.

In the end, the son who assured his mother he would stay nearby was present at her bedside when she passed away in 2021, at home in the rectory.

“I was able to give her the last rites,” he said. “It was a gift to be able to do that.”

Msgr. Barrett has seen many changes in 47 years, especially in the racial diversity of clergy. With more Black priests, including many from African countries, and more Hispanic and Asian priests, he said, “now we look like the Catholic Church: universal. We are part of a global family.”

“I have been blessed by the prayers of many people in my life, and treated respectfully as a brother by every priest in the diocese,” he said. “I’m grateful for the friendships that transcend all barriers.”

Looking back on the “wonderful experience” of his priesthood, Msgr. Barrett said, “God truly has a plan for all of us.”