“Black history is and always has been Catholic history. Catholic history is and always has been Black history.”

Thus Shannen Dee Williams began her presentation on Saturday, Jan. 21, at Immaculate Conception Church (ICC), Hampton, as part of the parish’s Bishop Keane Institute lecture series. Williams, an associate professor of history at the University of Dayton, Ohio, with a doctor- ate in history from Rutgers University, is a historian of the African American experience and author of the book “Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle.”

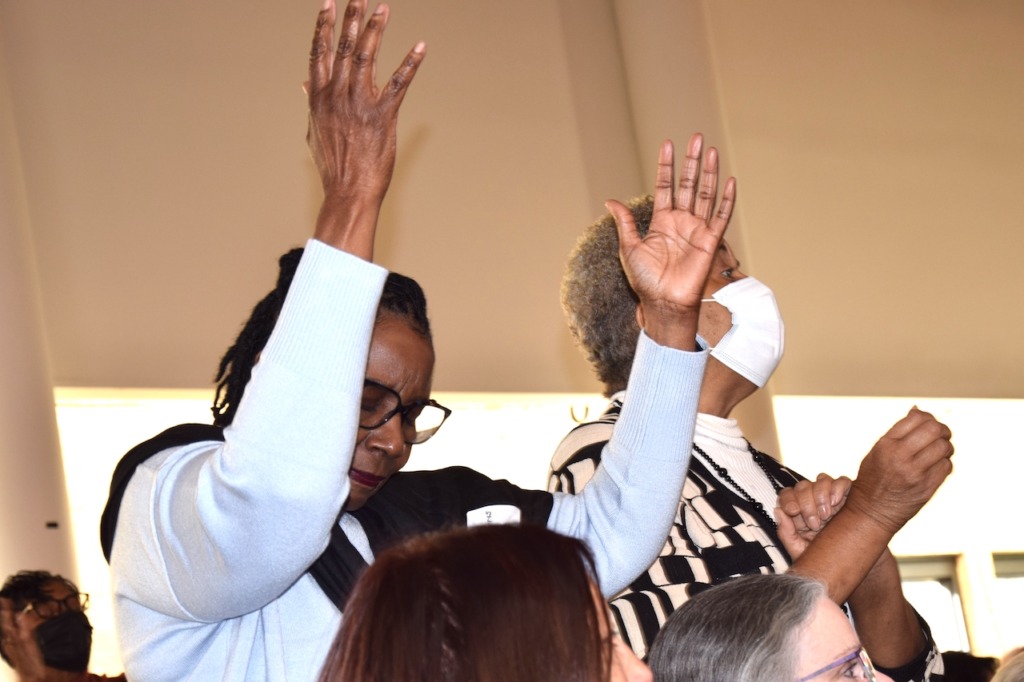

During her talk, Williams debunked what she called four myths about the Catholic Church regarding racism. Afterward, the approximately 250 attendees discussed three questions in small groups: What surprised you? What gives you hope? What is the Holy Spirit calling our Church to do?

Following that, summaries of the group discussions were given and Williams answered questions. Next was music and a prayer service in the spirit of African libation for which the choir of the Basilica of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception, Norfolk, sang. A lunch featuring traditional African fare concluded the morning.

“This event was important because it brings education and awareness to topics in areas of the Church that tend not to be heard or seen,” said Daniel Villar, director of the Diocese of Richmond’s Office of Ethnic Ministries.

Disspelling myths

Williams said one myth is, “Black Catholic history in the United States is inconsequential and primarily a 20th-century story of the conversion of African American southern mi- grants in the urban North, West and Midwest.”

She said in actuality when the Spanish founded St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565, some of the earliest generations included free and enslaved Black Catholics. She also spoke of historical events like the Stono Rebellion of 1739 started by “Congolese Catholics” trying to get to St. Augustine because they were promised to be freed there if they took up arms against the British. She mentioned people like a Black sister who in 1820 founded the nation’s first Catholic school for Black girls in Washington, D.C., when she was 15.

“At every turn, African-descended people are represented in the earliest records of our Church,” Williams said.

A second myth, Williams said, is that “the Church was a reluctant and benevolent participant in modern slavery.”

To the contrary, she claimed the Catholic Church was among the “largest corporate slaveholders in America.” For example, Catholic laity and religious were among the largest enslavers in the nation, with the Jesuits having the most slaves in the Western Hemisphere in 1767.

When Pope Nicholas V’s papal bull “Dum Diversas” in 1452 authorized Portugal to conquer Saracens, it allowed the country “to invade and enslave and put into perpetual servitude any non-Christian in Africa,” and Pope Alexander VI in 1493 “extended much of these doctrines into the Americas,” she said.

Even though Pope Gregory XVI condemned slavery in 1839, that came 337 years after slavery formally began, she noted.

Segregation and exclusion

According to Williams, a third myth is “the Catholic Church was at the forefront of desegregation in the 20th century.” Although her research has uncovered “extraordinary” examples of Church officials taking “an unpopular stance for racial justice,” Williams said “over and over” she has found that the Catholic Church was the “largest practitioner of segregation.”

Another myth is “Catholic sisters were the moral compass of the Church in the fight for racial justice.” In actuality, eight historically Black sisterhoods (three of which exist today) in the United States were established because of the prohibition of Black women in white women’s religious communities, she said.

Although many orders denied Black women entrance, some in the 19th century allowed them to enter, but most of those Black women were “ambiguous,” she said. Likewise, in most cases before World War II, Black women who entered white religious orders had to “pass as white” and often had to cut ties with their families who were “noticeably Black.” Most decided not to join, Williams claimed.

Contemplative communities were the first to desegregate, and a nursing school in St. Louis was the first community in public ministry to admit visibly Black people, but they did so on a segregated basis. Williams maintains that “informal policies” against the admission of Black women into white religious communities in the United States still exist.

“For today, I want to leave you with these stories of faithfulness and these testimonies of courageous and tenacious faithfulness in hopes that we understand certainly that we can gather from Black Catholic history the courage, the strength, but also a blueprint for confronting the enduring sense of white supremacy and exclusion in our Church and our wider society,” she said.

‘Step out of the comfort zone’

During their breakout sessions, attendees concluded that hard conversations like this must continue even if it makes people uncomfortable.

“If we don’t know our history, if we don’t know the story of different peoples within our Church, we tend to minimize them and in doing so we tend to minimize what it means to truly be a universal community in Christ,” Father John Grace, ICC pastor, told The Catholic Virginian.